The bond market’s rout has gone too far, so look for interest rates to decline in coming months.

If that happens, it certainly would be good news to beleaguered retirees and near-retirees who have an outsize portfolio allocation to bonds. As they already know all too well, long-term bonds have lost just as much as the stock market this year—and therefore failed to provide conservative investors with any protection against the bear market on Wall Street.

Read: What can retirees do about inflation?

There are several reasons to believe that bonds’ bear market has gone too far, and I’ll discuss two of them in this column. The first is that real interest rates—nominal interest rates minus the expected inflation rate—recently have turned significantly positive. More often than not historically, nominal interest rates have declined when real rates are positive (and vice versa).

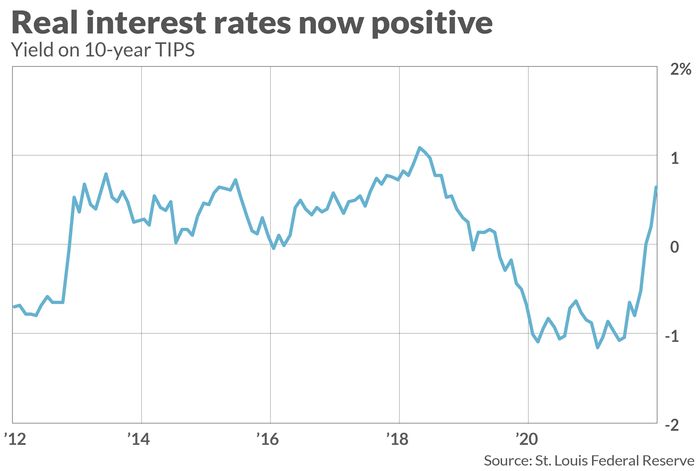

To appreciate where real interest rates are currently, take a look at the accompanying chart which plots the yield on the 10-year TIPS. This is a real yield, since TIPS’ principal is indexed to inflation. So when the TIPS yield is positive, as it is now, it represents the amount investors are demanding above and beyond inflation.

Note carefully that you can’t attribute the increasing real yield to the latest CPI numbers, which show that inflation is running at the highest pace in over four decades. Since TIPS are indexed to the CPI, they are automatically hedged against those increases. The quoted TIPS yield represents what additional amount investors receive besides inflation.

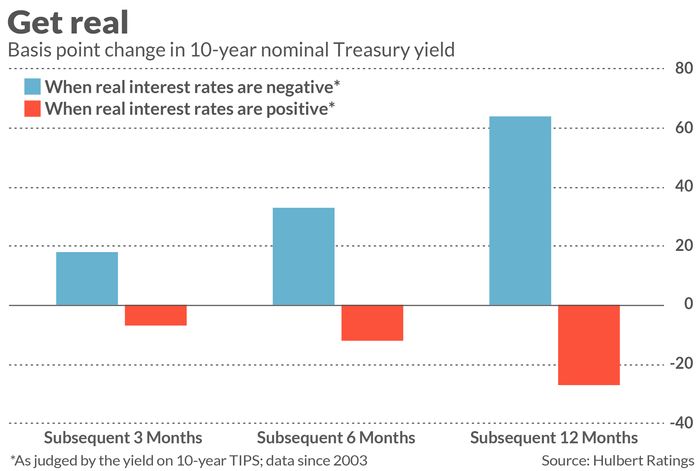

To demonstrate that positive real rates are usually followed by declining nominal rates, I segregated monthly levels of the 10-year TIPS yields over the last 20 years into two groups: The first had all those in which the yields were negative, while the second had all those in which the yields were positive. For both groups I measured average changes in the nominal 10-year yield over the subsequent 3-, 6- and 12-month periods.

The results are plotted in the accompanying chart. Sure enough, the nominal 10-year yield has tended to fall when real yields are positive, and vice versa. These differences are significant at the 95% confidence level that statisticians often use when determining if a pattern is genuine.

Interest rates during recessions

The second reason I want to mention for thinking that bonds will rally in coming months is that a recession seems increasingly likely. George Saravelos, global head of currency research at Deutsche Bank, reports that, on his interpretation of how various futures contracts are trading, the markets now place the odds of a recession before the end of this year at 100%.

Far more often than not, interest rates decline during recessions. Consider the 17 recessions over the last century in the calendar maintained by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the semiofficial arbiter of when U.S. recessions begin and end. Nominal yields on the 10-year Treasury declined in all but one of them.

This one exception was during the recession that lasted from November 1973 to March 1975, which marked the beginning of the stagflation era. Since some today are worried that we may be entering a similar period, this exception does seem ominous. I am tempted not to put undue importance on it, however, since interest rates declined in the other two recessions that also occurred in the decade that lasted from 1973 to 1982.

Another reason not to exaggerate the importance of that one exception: Upon analyzing all recessions in the NBER calendar, I found no statistically significant correlation between the magnitude of inflation and how the 10-year yield fared during the recession. For example, during another of the recessions that occurred during the stagflation decade—the one that lasted from January through July of 1980—inflation was running at a double-digit rate but the 10-year yield still fell.

None of these tea leaves provides a guarantee that interest rates will decline in coming months. And even if rates do decline in coming months, these tea leaves shed no light on the bond market’s long-term prospects. Still, it’s encouraging that compelling reasons have emerged that provide substance to the hope that, for the moment at least, the worst of the bond bear market is behind us.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected].