Five times in the past year, investors and traders hoped the Federal Reserve would shift to an easier policy stance at some point and were wrong. While it remains to be seen what happens this time, inflation’s historical record suggests financial markets, policy makers and forecasters are still much too sanguine.

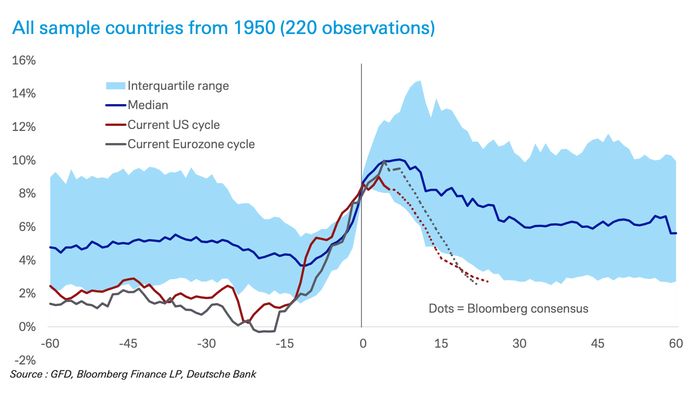

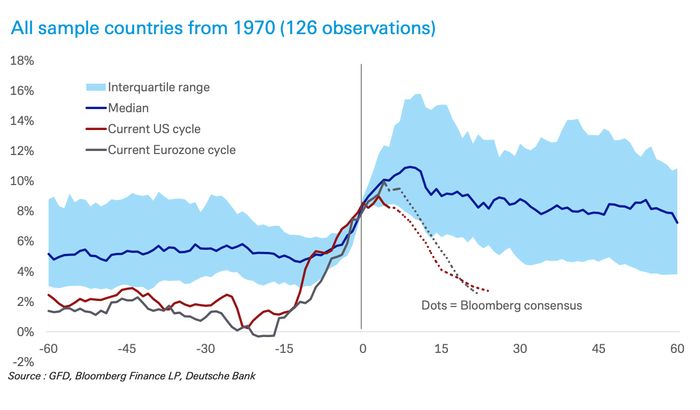

Inflation generally takes about 2 years to fall back below 6% when it spikes above 8% before settling around that level for up to five years, based on the median result of data compiled from 50 developed- and emerging-market countries, according to Deutsche Bank researchers Jim Reid, Henry Allen and Galina Pozdnyakova. Some of that data stretches as far back as a century, they said.

The multiyear record of inflation clashes with the current thinking of economists, traders and policy makers themselves, who fueled the latest speculation about a Fed “pivot” last Friday by opening the door to a debate on the size of December’s rate hike at their Nov. 1-2 meeting. Financial markets have been quick to react: U.S. stocks were up Tuesday morning and headed for a third straight session of gains, Treasury yields pulled back, and fed-funds futures traders briefly priced in a better-than-even chance of a 50-basis-point December rate hike instead of another 75-basis-point move.

Read: Here are the 5 times traders and stock-market investors got fooled by Fed ‘pivot’ hopes in past year

For now, the consensus view is that inflation should drift back down to 3% or even lower within just two years. And there’s an abundance of views to support the widespread expectation that price gains are set to ease — like those from Daniel Silver, Michael Hanson and Phoebe White at JPMorgan Chase & Co. JPM, who cited declining energy prices, easing supply-chain distortions, and a stronger U.S. dollar as just a few of the reasons that an “inflation downshift is on its way.”

The major caveat, though, is that inflation has surprised repeatedly to the upside this year, with the exception of July’s downside surprise. The topic of persistent price gains dominates earnings calls, though some companies have held up better than expected, after seven straight months of 8%-plus annual headline readings from the U.S. consumer-price index. And inflation is either still raging or not slowing fast enough outside the U.S. — from the eurozone and the U.K. to Canada and Brazil.

Meanwhile, the definition of a Fed “pivot” has changed over the past 12 months. Last November, at a time when major central banks had yet to start tightening, a pivot was considered to be a later-than-expected “liftoff” or initial rate hike during 2022. Now that the Fed has delivered three straight hikes of three-quarters of a percentage point each since June, and a fourth is all but certain on Nov. 2, the definition of a “pivot” has evolved to mean a shift away from that increment. Earlier on Tuesday, for example, fed-funds futures traders began pricing in a 52% chance of a smaller 50-basis-point December hike before dropping that likelihood to 48% by midday.

Deutsche Bank

DB,

a self-described outlier on Wall Street that predicted in June that inflation would fail to decelerate, looks at how inflation has behaved through 2019 from three different starting points —1920, 1950 and 1970. To avoid “double-counting,” Deutsche Bank’s researchers said they only considered inflation moves above 8% when there hadn’t been another move above that level in the previous 12 months. In each instance, inflation exhibited a similar pattern of remaining persistently high for years, based on charts containing the number of months before and after inflation moved above 8%.

Source: Global Financial Data, Bloomberg, Deutsche Bank

Source: Global Financial Data, Bloomberg, Deutsche Bank

Source: Global Financial Data, Bloomberg, Deutsche Bank

“Should we have been so surprised by the stickiness of inflation?” the researchers wrote in a note released Tuesday. “History would suggest no, as when inflation has previously gone to levels as high as it is right now, it’s usually been slow to drift lower again. Furthermore, it usually ends up settling at a level some way above where it was before the inflation spike began.”

“History never repeats exactly, but since inflation forecasting has generally been so poor over the last 18 months, it’s worth us asking what normally happens when inflation breaches these thresholds,” they said. “The answer is that it’s normally quite sticky, especially in the post-1970 period.”

Whether it’s the historical evidence or the consensus expectations that prove to be more accurate “will have a profound impact on financial markets and economies over the next few years,” Reid, Allen and Pozdnyakova wrote. If the median inflation outcome cited in Deutsche Bank’s paper proves correct, “then the turbulence of 2022 could prove to be just the beginning.”

As of Tuesday afternoon, all three major stock indexes

DJIA,

COMP,

were headed for a higher finish, led by a 1.5% gain in the Nasdaq Composite, while investors sent the benchmark 10-year yield

TMUBMUSD10Y,

below 4.1% and policy-sensitive 2-year rate

TMUBMUSD02Y,

to 4.5%.