Don’t jump into stocks every time the market mounts a sizeable rally during a bear market. All too often those rallies turn out to be nothing more than bear-market traps, luring gullible bulls back into equities before the bear market resumes in earnest. Bear markets don’t end until frustrated investors throw in the towel.

The U.S. market rally between June 17 and June 24 may be the latest of these bear-market traps. In that week-long rally, the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

rose 5.4% and then almost immediately started to retreat. Investors are sitting on a loss if they got into stocks on June 24, when the Dow rose 5% above its prior low.

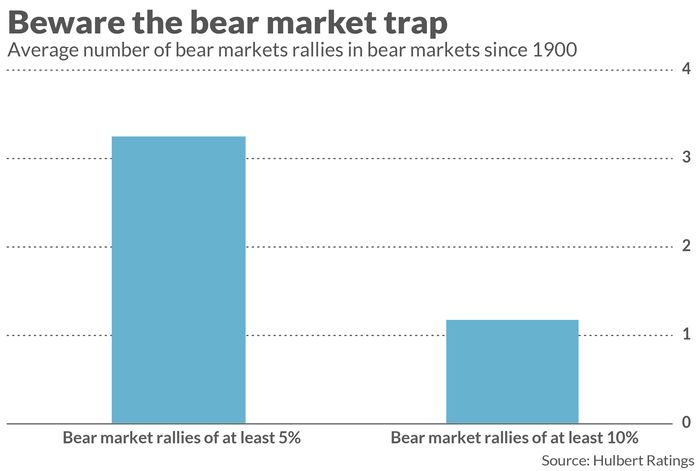

Consider the 37 bear markets since 1900 in the calendar maintained by Ned Davis Research. During each of these bear markets, I counted the number of times the Dow rallied at least 5% from a new low. On average, each bear market experienced more than three such rallies, with one occurring between every four to five months.

Ten percent rallies were not as common, not surprisingly, but not rare. The average bear market since 1900 experienced between one and two rallies in which the Dow rose by more than 10% before succumbing to the ongoing bear market.

Note that calculating the number of rallies that occur in bear markets depends crucially on how they are defined. One important variable is how long after one 5% rally has taken place before you begin to look for another one. For this column, I focused only on rallies that occurred from new bear market lows, which is a conservative way of counting the rallies. The number of bear-market rallies also depends on the market average on which you focus.

The 2007-2009 bear market during the Global Financial Crisis provides a good illustration of the frequency of bear-market rallies. During this period there were eight times when the Dow rallied at least 5% from a new low, and four in which the market rallied at least 10%.

By that bear market’s final low in March 2009, many beleaguered investors had sworn off of equities altogether, claiming they’d never trust the stock market again.

These historical statistics don’t tell us whether this current bear market is close to ending or whether more carnage is ahead. But what the data do teach us is that powerful rallies are not a reliable signal of whether a new bull market has begun.

The data here dovetail nicely with my column several weeks ago on the historical tendency for the most explosive daily jumps in the market to be concentrated during bear markets. I pointed out that over the past century, 58% of the trading days with the biggest percentage gains occurred during bear markets. That’s double the proportion you’d expect if big daily spikes occurred randomly.

The bottom line? Think of bear markets as mischievous beings, designed to continually give you hope and then dash it. Once again we’re shown the importance of having an investment strategy that we follow with discipline through thick and thin. Only then can we resist the perverse temptations of the bear market.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected]