The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision that overturned a half-century of abortion rights has sparked intense and opposing emotions. We find ourselves, yet again, in a polarized political fight with the battlegrounds in Congress, in the boardrooms, on the streets, on social media and, for some of us, at our kitchen tables.

Yet the problem is not in the clarity and conviction of either side — it’s in the lack of connection across sides.

People are flattening the issue of abortion into a single either/or decision: choice or life, a simplicity reinforced by newspaper headlines and social media one-liners. Then people divide the population into those aligned and those against, dehumanizing “them” on the other side of the debate while rarely having deeper conversations to learn what “they” really think.

The result is trench warfare; each side digging deeper in defense and blindly shooting down the others.

To be sure, taking a stand on abortion — or any other controversial issue — is important and valued. We bring our personal experiences, moral principles and political beliefs to inform our varied, often disparate thinking. Yet abortion is a complex issue. Most Americans hold nuanced views of contextual and timing conditions, and how that access should be adjudicated, with perspectives often much more moderate and complex than reflected by the Supreme Court, political debates or newspaper headlines.

The polarization of either/or decisions and reinforcing social groups obscures nuance. It also prevents us from creating more policies that can sustain over time.

We have spent the last 25 years studying how people face such complex and tenuous issues. Our research shows that when decisionmakers engage opposing positions and adopt what we call both/and thinking, they generate more sustainable and creative solutions.

If we, as a society, are to bridge our divides and engage both/and thinking then we need more insightful and productive political deliberations.

Doing so requires that people first surface and honor differences via one-on-one conversations. This means finding and connecting to those with opposing points of view. Then we must respectfully listen to what they think. We don’t need to agree. In fact, we probably won’t. However, as our research shows, people have applied robust both/and solutions start with recognizing and value differences.

For example, Sharon Browning launched the organization Just Listening to help foster connections and learn listening skills across all kinds of issues. As she describes, “listening is an act of justice” offering respect to those we listen to. Browning has brought groups of Jews to Palestinian territories to hear their stories, finding that even if they did not agree, they could build deeper empathy and connection by listening to one another.

Margaret Seidler and Police Chief Greg Mullen took this a step further to bridge racially charged divides in the city of Charleston, South Carolina after the 2015 shooting of nine congregates of the AME Mother Emanuel Church in 2015.

Working in partnership with Jake Jacobs Consulting, Seidler and Mullen ran 33 “listening sessions” across the city where citizens and police — groups often at odds with one another — came together to hear each other’s fears, goals and experiences. They surfaced differences, fostered connections, and sought more effective solutions for their common desires to create a safer city and stronger community.

These listening sessions led to 86 new strategies to implement community policing in the city, changing policing and the participation and collaboration of citizens. They called this work The Illumination Project, aptly named for how it surfaced both profound insights and impacts.

Harvard Business Review Press

Organizations can also play a role, helping members develop skills for learning across differing positions and then creating the conditions to do so. Entrepreneur Kerry Ann Rockquemore knew that her organization, the National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity, was filled with divergent perspectives, opinions and ideas. She also knew that creative decision making depended on surfacing, rather than burying, such differences, but that people often avoid conflict.

In response, everyone in the organization was trained in the art of “healthy conflict” to respectfully share opposing views. These practices helped them work through their tensions on work projects, as well as around difficult political and personal issues.

The vicious cycles of constant fighting surrounding polarized political issues leave everyone worse off. The antidote requires that we find both/and possibilities, starting with honoring and valuing differences.

Such both/and thinking is not easy. But in the end, it is worth it. It may be in such a crisis of polarization as in the abortion discussion where we have hit rock bottom, that we can start listening to one another and working together across our differences.

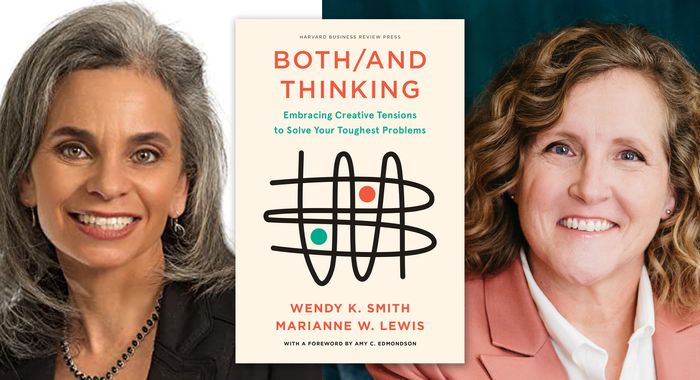

Wendy Smith is the Dana J. Johnson Professor of Management at the University of Delaware’s Lerner College of Business and Economics. Marianne Lewis is the dean and professor of management at the University of Cincinnati’s Carl H. Lindner College of Business. They are the authors of “Both/And Thinking: Embracing Creative Tensions to Solve Your Toughest Problems”.