It would be great if we got along with everyone we worked with, but the reality is that we’ve all been on a team or in an organization with someone (or several people) who we find difficult, perhaps even toxic. These people not only make work unpleasant but there are physiological and emotional costs to toiling alongside them. Georgetown University professor Christine Porath’s research on incivility shows that the greatest impact is often to the person who is being mistreated.

There can also be a financial toll to dealing with difficult people. This is, in part, because the energy it takes often means you have less time and fewer cognitive resources to focus on your career. But it’s also because there’s a risk that, in calling out a colleague’s challenging behavior, you get labeled as the “difficult person.” And when you’re seen as “part of the problem” or someone who is “making waves,” you’re more likely to miss out on opportunities like raises and promotions — or even get fired.

Take, for example, Clara (not her real name), who was brought into a small manufacturing company to revamp their HR department only to find out that one of the company’s partners had no interest in changing. He consistently put down her ideas and accused her of not knowing what she was doing. When she raised the issue with his co-owners, they dismissed her concerns and told her “that’s just the way he is.” After several months of this, she was asked to accept a severance package because the owners didn’t think the “friction was solvable.” As Clara explained “my ‘complaining’ about this owner made me seem like a target and part of the problem.”

Bringing up concerns can be a particularly risky endeavor if you’re a member of an underrepresented group and you’re calling out difficult behavior that is related to bias. This is why it’s so critical that allies speak up.

This doesn’t mean you need to, or should, stay quiet. On the contrary, you can find productive ways to address your colleague’s behavior and escalate issues when necessary — but only to people you know are motivated and skilled enough to do something about the situation. Here’s how to protect yourself:

1. Clearly assess the risks: Pointing out hostile or rude behavior could impact your relationships and standing with your coworkers or boss, your performance reviews, job assignments, or even whether you keep your job. Develop a realistic picture of the danger you’re facing, while also considering the risks of not saying something. What are the consequences of staying silent? Perhaps not speaking up would violate your personal values or by letting the behavior pass, you appear as if you condone it. Or maybe you’re experiencing mental and physical symptoms from the stress, and not speaking up would only exacerbate those.

2. Document transgressions: It’s helpful to have a record of bad behavior, especially if you need to make the case to those in power. When your colleague oversteps, note the time, place, and what was said or done. Don’t just record their actions, write down what you said and did in response. Leaders will be more willing to intervene if they see a pattern of behavior and know that you — and perhaps others — have already taken steps to address it.

3. Choose who you raise the issue with carefully: Ideally, you want to go to someone who has the power and skills to do something, whether that’s your boss or another manager who can provide you with advice, give direct feedback to the difficult coworker, or reprimand them. Who is the right person or department to go to? Your boss? Your boss’s boss? An HR representative? Will they be open to helping you? Will they be discreet? Do they have the skills to give your difficult colleague feedback? Are they sufficiently motivated to take action?

Before approaching someone who you think fits the bill, look into how they’ve responded to comparable situations in the past. Did they give good advice? Did they follow through if they offered assistance? Did they make things better, or perhaps worse? The answers to these questions will help you decide whether it’s a good idea to escalate or not.

Harvard Business Review Press

Back up your claims

It helps to tie the problems to concrete business results. Articulate how the person is damaging the team’s performance and provide plenty of evidence to back up your claims (this is where your documentation will help). It’s more convincing if your account of events can be corroborated, so confirm that others have witnessed the negative behavior and are willing to stand with you if need be.

Sometimes your endeavors to involve higher-ups might backfire or boundaries you clearly set are violated anyway. In those cases, it’s time to batten down the hatches and focus on protecting yourself and your career. Remember: Whether you’re just starting to address the negativity or you’ve been trying to change things for years, your health and well-being should always be a priority.

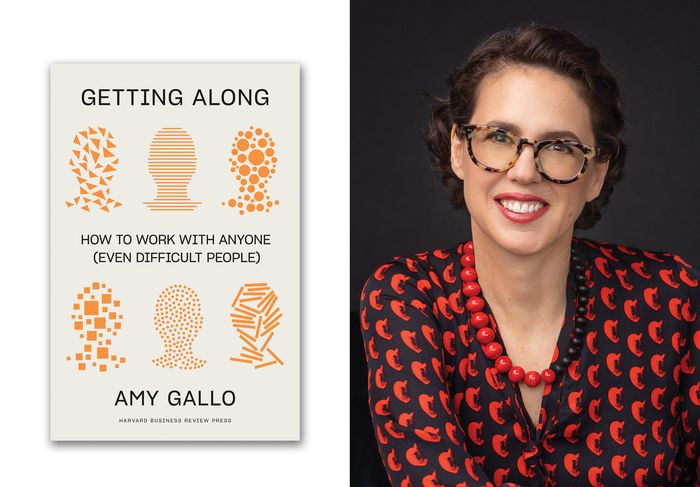

Amy Gallo is the author of Getting Along: How to Work with Anyone (Even Difficult People) (Harvard Business Review Press, 2022). She is a contributing editor at Harvard Business Review and cohost of the Women at Work podcast.

More: Men must hold other men accountable when they see women being harassed. Here’s what you can do

Also read: If your employer really wants to hire the best workers, here are 4 proven paths to success