The pace at which food prices rise matters not just because it directly impacts household budgets, especially for those at the lower end of the income distribution, but also because the visibility of food price changes helps to shape the public’s expectations of inflation which itself can contribute to higher inflation.

Annualized food inflation is now 8.8% in the U.S. and eurozone, up from an average of 1.6% in the decade before the pandemic.

The Facts:

Global food prices started to increase in mid-2021, but the war in Ukraine exacerbated these trends through its impact on commodity prices. The FAO Food Index, based on an average of commodity prices for meat, dairy, cereals, vegetable oils, and sugar, increased 60% since the beginning of 2020, raising concerns of growing hunger and poverty, particularly in less developed countries.

Much of the increase in food commodity prices was passed on into retail prices in many countries around the world. We are able to track daily changes in prices for food products sold online in a group of 23 large countries and find that retail prices for these products increased an average of 5% in the first five months of the conflict. (The countries included in the data are: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States, and Uruguay.)

Food inflation has begun to moderate in the developing world.

Econofact

The trajectory of food price inflation differs somewhat for the United States and the eurozone versus developing countries (see chart). Developing countries were immediately affected by the war. Daily food price indices constructed with online data show that retail food prices in the middle-income countries included in the sample quickly started rising at a higher rate, jumping over 4% in just the two months following Feb. 24, 2022, the day Russia invaded Ukraine. Because consumers in less developed countries spend a higher share of their income on food, the impact of rising food costs was significant and is already causing economic and political instability in countries like Argentina and Sri Lanka. (Food costs account for 17% of consumer spending in advanced economies, but over 20% in Latin America and Emerging Asia and 40% in sub-Saharan Africa.)

While it remains higher than at the start of the pandemic, food inflation has started to decline for the emerging economies in our sample, consistent with the decline in food commodity prices of recent weeks.

Relative to historical standards, the increase in food inflation has been greater for developed countries. Annualized food inflation is now 8.8% in these countries, up from an average of 1.6% in the decade before the pandemic. And, while food inflation has shown declines in the most recent data for emerging economies, it remains stubbornly high for the United States and the eurozone continuing to increase at a rate of over 1% per month.

Shortages of food products have increased again.

Econofact

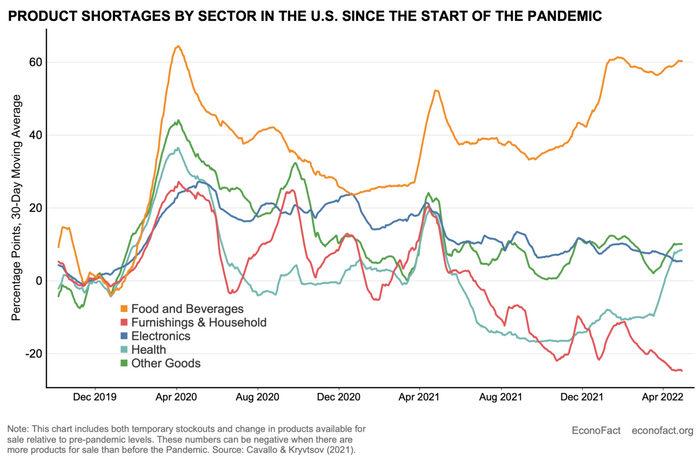

One reason for the more persistent food inflation in developed countries may be the persistence of supply disruptions and shortages of food products that began with the pandemic. The pandemic disrupted the flow of goods along international supply chains, increased the cost of domestic business operations and undercut retailers’ efforts to manage inventories. These difficulties could cause higher production costs, difficulties in restocking, and product scarcities, and result in retailers passing costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices (see here).

While shortages of most categories of goods have abated from their pandemic highs, food shortages have been increasing again in the United States since September 2021 and remain abnormally high, with more than 60% of pre-pandemic food product varieties remaining out of stock or discontinued, a level close to the peak at the beginning of the crisis (see chart below).

Differences in controls over fuel prices could also be contributing to the divergence in food inflation trends between developed and emerging economies. Fuel prices affect food inflation because transportation costs are an important share of the total cost of production of food sold in retail markets. The war led to a more dramatic and persistent increase in fuel prices at the pump in developed economies relative to many developing countries where retail fuel prices are highly regulated and therefore did not increase much in the first five months of the war. Although they have been stabilizing in recent weeks, fuel prices in developed economies still remain above prewar trends.

Food prices matter not only because they are an important part of most consumers’ consumption baskets, but also because persistent levels of food inflation can lead to higher inflation expectations and eventually contribute to an upward inflation spiral. How people believe prices are going to behave in the future plays an important role because inflation expectations can sometimes become self-fulfilling. Workers who expect to be facing higher prices for the products they buy, might demand higher wages, which leads to increasing production costs and higher product prices, for instance.

A growing body of research finds that consumers often rely on a few key products they consume regularly to extrapolate changes in the overall cost of living (see here). Research finds that consumers who experience extreme changes in grocery prices are more likely to base inflation expectations on those changes than those who see little or moderate grocery-price movement.

What this Means:

The pandemic and the War in Ukraine continue to put significant pressure on global food inflation. These price increases have already caused unrest and political pressures in many countries and may contribute to a persistent increase in inflation expectations. The pressure is shifting to advanced economies, which are experiencing levels of food inflation that are worse by historical standards. These trends show few signs of slowing in the short run, suggesting the pressure will remain for the remainder of 2022.

Alberto Cavallo is an associate professor at the Harvard Business School. He was co-founder of the Billion Prices Project.

Editor’s note: The stockout analysis in this memo updates results from: Cavallo A. and Kryvtsov O. “What Can Stockouts Tell Us about Inflation? Evidence from Online Micro Data.” NBER Working Paper 29209, September 2021.