That’s the big question facing policy makers, investors and consumers.

Unfortunately, the way we talk about the inflation numbers — released Thursday — can confuse as much as it can clarify. If we focus our attention on how much inflation we’ve already endured, we may miss clues about how much inflation we have yet to endure, which is the most important question.

Instead of concentrating on the here and now, most reports put the year-on-year inflation rate in the headline.

Not to pick on anyone, but here’s how The New York Times reported Thursday’s report on the consumer price index: “Consumer prices rose 8.2 percent in the year through September, in a report that dashes hopes that inflation in the U.S. may be slowing down.”

That’s not wrong, but it’s seriously misleading. I’ll show you a more useful way to think about the numbers.

“ The Fed has actually hit its 2% target over the past three months, but of course the Fed is concerned that inflation could accelerate from here, especially in the hugely important shelter category, where hot inflation for the next year or so is baked into the cake. ”

Making sense of economic data is often a matter of finding the right context, which means the first thing you should do is ask yourself how you want to make use of the data. There are several correct ways of displaying the data, but some are better than others at answering specific questions.

What’s inflation done over the longer run?

For instance, if we want to know how much inflation we’ve already endured, it might be best to look at the year-on-year increase in the CPI. (The same logic in this column applies to the Fed’s preferred measure, the personal consumption expenditure price index.) We would compare current prices with prices a year earlier. This may be the most common way the CPI is reported in the media right now, because it puts the intensity and persistence of inflation into a perspective that readers can relate to.

This method answers the question: How far have we come?

In this case, we would find that consumer prices have risen 8.2% since September 2021. That’s very high inflation, but it’s lower than the 9% year-on-year increase recorded in June, which was a 40-year high.

MarketWatch

If we looked just at the year-on-year increase in the CPI, we might agree with the Federal Reserve’s assessment that there hasn’t been an “appreciable decline” in bringing inflation down to the 2% target.

The year-on-year perspective is good for seeing how far we’ve come, but it’s not so good at predicting where inflation is going, because it’s essentially a backward-looking measure. It gives equal weight to inflation in September 2021 and inflation in September 2022. Yet the inflation rate from a year ago has little bearing on what the inflation rate will be going forward.

The best predictor of this month’s inflation rate is last month’s inflation. The CPI is dominated by so-called sticky prices that don’t change very often. Inflation is pretty persistent from month to month.

What’s inflation doing lately?

So if we wanted to know how hot inflation has been running lately, we’d look at a shorter period of time, say, one month. The media frequently report the CPI this way, using the month-to-month percentage change rather than an annual rate.

In this case, the data would say that the CPI rose 0.4% in September after a 0.1% increase in August.

MarketWatch

But using the monthly percentage change seems like a weird choice when we use annual rates for the year-on-year gain. It’s like talking about miles-per-hour and then switching to feet-per-second.

That’s why many analysts prefer to convert the monthly change into an annual rate so that it’s comparable to the year-on-year inflation rate. The data say that the CPI rose at an annual rate of 4.7% in September versus the 17.1% pace in June, which was a 17-year high.

MarketWatch

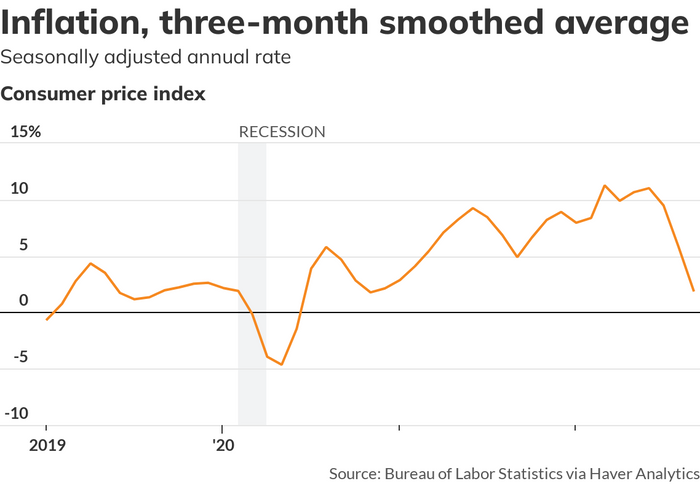

The monthly data seem awfully noisy. So let’s find the underlying trend by taking a three-month average to smooth out the bumps. In this case, the data say that the CPI rose at a 2% annual rate from July through through September, down from 11% in June and 11.3% in March, which was a 41-year high.

This perspective answers the question: What’s happening with inflation yesterday, today and tomorrow?

If we look at the three-month smoothed annual rate, we might disagree with the Fed about how much progress they’ve made. Going from 11.3% in March when the Fed started raising interest rates to 2% now isn’t nothing. It looks like — dare we say it? — progress.

The Fed has actually hit its 2% target over the past three months, but of course the Fed is concerned that inflation could accelerate from here, especially in the hugely important shelter category, where hot inflation for the next year or so is baked into the cake.

What question do we want to answer?

All these measures of CPI are correct; they just come from a different perspective. Which one should we pay attention to? The one that says no appreciable progress has been made, or the one that says some-but-not-enough progress has been made? If we have a bias toward which story we want to tell, the answer is obvious.

But if we want an honest account, we’ll use the perspective that answers the question we are asking and let the chips fall where they may. (What you don’t do is start with the answer you want and then work backwards.)

That’s why I think the best way to think about the inflation we’re seeing now — and which is likely to persist in the near future — is to look at the three-month smoothed, seasonally adjusted annual rate.

That perspective is a lot more honest than the other way, and it’s a lot more hopeful, as well.

Rex Nutting is a columnist for MarketWatch who’s been writing about the Fed and the economy for more than 25 years.