With the S&P 500 holding above 4,000 and the CBOE Volatility Gauge, known as the “Vix” or Wall Street’s “fear gauge,”

VIX,

having fallen to one of its lowest levels of the year, many investors across Wall Street are beginning to wonder if the lows are finally in for stocks — especially now that the Federal Reserve has signaled a slower pace of interest rate hikes going forward.

But the fact remains: inflation is holding near four-decade highs and most economists expect the U.S. economy to slide into a recession next year.

The last six weeks have been kind to U.S. stocks. The S&P 500

SPX,

continued to climb after a stellar October for stocks, and as a result has been trading above its 200-day moving average for a couple of weeks now.

What’s more, after having led the market higher since mid-October, the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

is on the cusp of exiting bear-market territory, having risen more than 19% from its late-September low.

Some analysts are worried that these recent successes could mean that U.S. stocks have become overbought. Independent analyst Helen Meisler made her case for this in a recent piece she wrote for CMC Markets.

“My estimation is that the market is slightly overbought on an intermediate-term basis, but could become fully overbought in early December,” Meisler said. And she’s hardly alone in anticipating that stocks might soon experience another pullback.

Morgan Stanley’s Mike Wilson, who has become one of Wall Street’s most closely followed analysts after anticipating this year’s bruising selloff, said earlier this week that he expects the S&P 500 will bottom around 3,000 during the first quarter of next year, resulting in a “terrific” buying opportunity.

With so much uncertainty plaguing the outlook for stocks, corporate profits, the economy and inflation, among other factors, here are a few things investors might want to parse before deciding whether an investable low in stocks has truly arrived, or not.

Dimming expectations around corporate profits could hurt stocks

Earlier this month, equity strategists at Goldman Sachs Group

GS,

and Bank of America Merrill Lynch

BAC,

warned that they expect corporate earnings growth to stagnate next year. While analysts and corporations have cut their profit guidance, many on Wall Street expect more cuts to come heading into next year, as Wilson and others have said.

This could put more downward pressure on stocks as corporate earnings growth has slowed, but still limped along, so far this year, thanks in large part to surging profits for U.S. oil and gas companies.

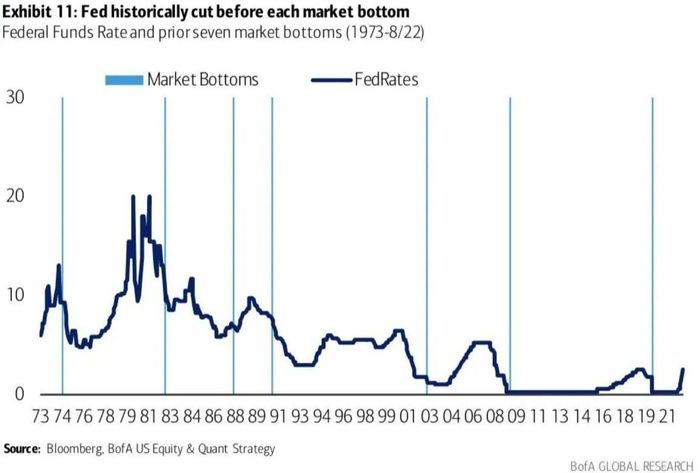

History suggests that stocks won’t bottom until the Fed cuts rates

One notable chart produced by analysts at Bank of America has made the rounds several times this year. It shows how over the past 70 years, U.S. stocks have tended not to bottom until after the Fed has cut interest-rates.

Typically, stocks don’t begin the long slog higher until after the Fed has squeezed in at least a few cuts, although during March 2020, the nadir of the COVID-19-inspired selloff coincided almost exactly with the Fed’s decision to slash rates back to zero and unleash massive monetary stimulus.

BANK OF AMERICA

Then again, history is no guarantee of future performance, as market strategists are fond of saying.

Fed’s benchmark policy rate could rise further than investors expect

Fed funds futures, which traders use to speculate on the path forward for the Fed funds rate, presently see interest-rates peaking in the middle of next year, with the first cut most likely arriving in the fourth quarter, according to the CME’s FedWatch tool.

However, with inflation still well above the Fed’s 2% target, it’s possible — perhaps even likely — that the central bank will need to keep interest rates higher for longer, inflicting more pain on stocks, said Mohannad Aama, a portfolio manager at Beam Capital.

“Everyone is expecting a cut in the second half of 2023,” Aama told MarketWatch. “However, ‘higher for longer’ will prove to be for the entire duration of 2023, which most folks haven’t modeled,” he said.

Higher interest rates for longer would be particularly bad news for growth stocks and the Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

which outperformed during the era of rock-bottom interest rates, market strategists say.

But if inflation doesn’t swiftly recede, the Fed might have little choice but to persevere, as several senior Fed officials — including Chairman Jerome Powell — have said in their public comments. While markets celebrated modestly softer-than-expected readings on October inflation, Aama believes wage growth hasn’t peaked yet, which could keep pressure on prices, among other factors.

Earlier this month, a team of analysts at Bank of America shared a model with clients which showed that inflation might not substantially dissipate until 2024. According to the most recent Fed “dot plot” of interest rate forecasts, senior Fed policy makers expect rates will peak next year.

But the Fed’s own forecasts rarely pan out. This has been especially true in recent years. For example, the Fed backed off the last time it tried to materially raise interest rates after President Donald Trump lashed out at the central bank and ructions rattled the repo market. Ultimately, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic inspired the central bank to slash rates back to the zero bound.

Bond market is still telegraphing a recession ahead

Hopes that the U.S. economy might avoid a punishing recession have certainly helped to bolster stocks, market analysts said, but in the bond market, an increasingly inverted Treasury yield curve is sending the exact opposite message.

The yield on the 2-year Treasury note

TMUBMUSD02Y,

on Friday was trading more than 75 basis points higher than the 10-year note

TMUBMUSD10Y,

at around its most inverted level in more than 40 years.

At this point, both the 2s/10s yield curve and 3m/10s yield curve have become substantially inverted. Inverted yield curves are seen as reliable recession indicators, with historical data showing that a 3m/10s inversion is even more effective at predicting looming downturns than the 2s/10s inversion.

With markets sending mixed messages, market strategists said investors should pay more attention to the bond market.

“It’s not a perfect indicator, but when stock and bond markets differ I tend to believe the bond market,” said Steve Sosnick, chief strategist at Interactive Brokers.

Ukraine remains a wild card

To be sure, it’s possible that a swift resolution to the war in Ukraine could send global stocks higher, as the conflict has disrupted the flow of critical commodities including crude oil, natural gas and wheat, helping to stoke inflation around the world.

But some have also imagined how continued success on the part of the Ukrainians could provoke an escalation by Russia, which could be very, very bad for markets, not to mention humanity. As Clocktower Group’s Marko Papic said: “I actually think the biggest risk to the market is that Ukraine continues to illustrate to the world just how capable it is. Further successes by Ukraine could then prompt a reaction by Russia that is non-conventional. This would be the biggest risk [for U.S. stocks],” Papic said in emailed comments to MarketWatch.