Not once or even twice, but at least FIVE times in the past 12 months, investors and traders have expected the Federal Reserve to shift toward a dovish, or easier, monetary policy at some point — only to be wrong.

Well, at least someone is keeping count.

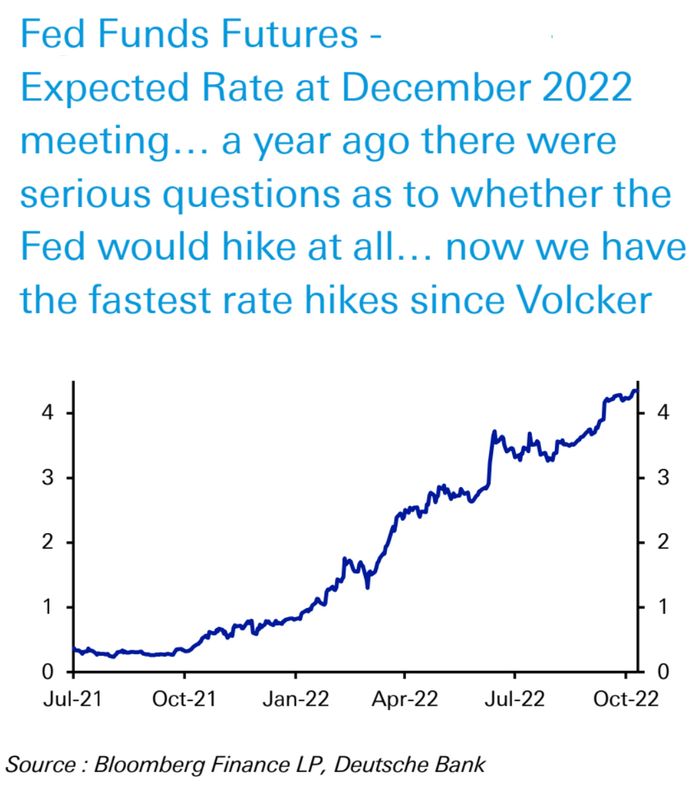

According to Deutsche Bank’s Henry Allen, the bottom line is that inflation is still too strong to let policy makers “pivot” in a durable manner. Even more troubling, every time the pivot narrative takes hold in financial markets, that loosens financial conditions and works against the Fed’s own efforts — making an actual pivot less likely, he said, in a Monday note.

“So when we hear about the sixth ‘pivot,’ it’ll be worth sounding a note of skepticism

as to whether the conditions are in place for it to be a lasting one,” wrote Allen, a research analyst.

Monday is a Columbus Day holiday, with the U.S. bond market closed and the stock market open. All three major stock indexes DJIA SPX COMP were posting sizable losses in afternoon trade, as investors brace for Thursday’s release of the September consumer-price index report. Economists and traders expect the report to contain the seventh straight annual headline inflation rate that’s above 8%.

In April, Frankfurt-based Deutsche Bank, generally regarded as Wall Street’s most pessimistic bank, became the first of its peers to call a U.S. recession during the current inflation era. Here is Allen’s list of each time since last November that investors and traders have seen their hopes dashed for a Fed shift toward easier policy:

Source: Bloomberg, Deutsche Bank

- November’s Omicron fears: On Nov. 26, 2021, the World Health Organization classified a new variant of COVID-19, Omicron, as a variant of concern. And within days, the first confirmed Omicron case in the U.S. was announced — raising widespread concerns that the pandemic was still not over. Though major central banks had not yet started tightening, fed-funds futures traders pushed back their expected timing of the Fed’s first rate hike in 2022 — to September from June — and stock investors sent the S&P 500 to an all-time high in December.

-

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: From late February to early March, after Russia invaded Ukraine, financial markets were more worried about the prospects of economic growth than they were about inflation. Some even questioned whether the European Central Bank would even be able to hike rates at all, according to Allen. Though the Fed did deliver a rate hike of just 25 basis points, or a quarter of a percentage point, in March — instead of the larger 50-basis-point move many expected — policy makers ultimately worried more about inflation’s persistence and signaled an aggressive path for rates ahead. Investors appeared to focus on only part of the Fed’s message: The S&P 500 advanced 3.6% for March, though it was down for the first quarter, while the yield on the 10-year bund

TMBMKDE-10Y,

2.346% ,

the German counterpart to Treasurys, moved back below zero. - May’s global-growth risks: Before anyone seriously talked about 75-basis-point rate hikes, investors were preoccupied with risks to growth, such as the invasion of Ukraine and China’s zero-tolerance approach to COVID. Futures traders began pricing in less tightening by the Fed and lowered their expectations for the total amount of tightening for the year. Mortgage rates dropped, and the S&P 500 gained 6.6% for the week that ended May 27. Ultimately, May’s CPI report surpassed estimates and paved the way for the Fed to hike by 75 basis points in June.

- Global recession concerns in July: Summer brought speculation about an imminent global recession, with oil prices falling from their peaks and helping the July CPI to come in lower than expected. This contributed to talk of a dovish pivot, which Jerome Powell seemed to confirm at July’s FOMC press conference by saying “it will likely become appropriate to slow the pace of increases” as monetary policy is tightened further. The S&P 500 jumped 9.1% in July, its largest monthly advance since news of a Covid-19 vaccine in November 2020, until members of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee pushed back on this interpretation. In August, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell delivered a very hawkish speech during the central bank’s Jackson Hole symposium that tried to put to rest any remaining hopes that policy makers might shift their policy stance.

- Major market turmoil: Here we are now, the month after September’s massive cross-asset selloff created chatter that something might be about to break in financial markets, particularly after turmoil in U.K. bond and currency markets. Those worries led financial-market participants to price in more rate cuts for 2023, as well as a brief surge in equities this month. The S&P 500 gained a combined 5.7% on Oct. 3 and 4, marking its biggest 2-day rally since April 2020. However, Fed officials pushed back again, with San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly saying “I don’t see that happening at all” when asked about rate cuts, and Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari adding that “until I see some evidence that underlying inflation has solidly peaked and is hopefully headed back down, I’m not ready to declare a pause.”