The energy and materials sectors might struggle the next few years as inflation and aggressive interest-rate hikes lead to a sharp global slowdown, warned an economist at Capital Economics.

The S&P GSCI energy spot index

SPGSEN,

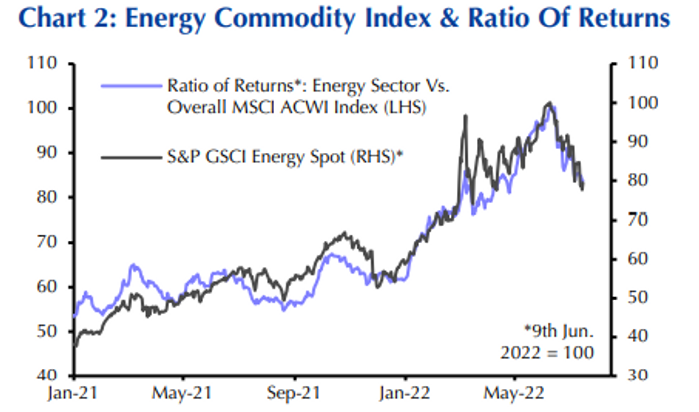

which tracks prices for oil and its derivatives, peaked on June 9. While it still trades over 40% higher year-to-date, it’s down by 17% since its peak. Industrial metals have also retreated from their peak by around the same amount, noted Oliver Allen, senior markets economist at Capital Economics, in a Tuesday client note.

SOURCE: REFINITIV, BLOOMBERG, CAPITAL ECONOMICS

That doesn’t spell good news for the energy and materials sectors.

“Although we doubt that they will fare quite as badly as they have in recent weeks, we still expect the energy and materials sectors of global stock markets to underperform over the next couple of years,” Allen wrote. “Worries that high inflation, and the large interest rate hikes required to tackle it, will lead to a sharp global slowdown have sent the prices of industrial commodities crashing down to earth in recent weeks.”

Earlier this month, growing recession fears and a drop in energy demand led to a slump that sent the U.S. crude benchmark back below $100 a barrel and into a bear market. Oil rebounded Monday after Saudi Arabia, the world’s top crude oil exporter, signaled it wasn’t prepared to significantly boost output following President Joe Biden’s visit late last week, but were back under pressure during Tuesday’s session.

West Texas Intermediate crude for August delivery

CL00,

CLQ22,

fell 1.3%, to $100.72 a barrel on the New York Mercantile Exchange on Tuesday afternoon, while global benchmark September Brent crude

BRN00,

BRNU22,

lost 1.2%, to trade at $107.45 a barrel on ICE Futures Europe.

Energy stocks are highly correlated to the price of energy commodities, and of oil in particular. As oil soared over the first half of the year, hitting 14-year highs in March, the energy sector also rallied. It remains the top performing sector in the S&P 500 with a year-to-date gain of nearly 30% but has pulled back more than 21% from its peak. The S&P 500

SPX,

is down around 17.6% for the year to date.

Indeed, high correlation to crude oil prices can be a double-edged sword, as energy stocks have underperformed considerably as crude has weakened, Allen said.

SOURCE: REFINITIV, BLOOMBERG, CAPITAL ECONOMICS

“We suspect that energy stocks will underperform the broader stock market by a bit more over the next few years, as oil prices grind lower,” wrote Allen. “Although sanctions on Russia complicate the picture, we envisage a backdrop in which demand growth generally softens, at the same time as oil supply, especially from the U.S. and OPEC+, gradually increases from current levels. Our forecast is that the price of Brent crude will dip from [around] $105pb (per barrel) at present, to $100pb by the end of this year, and $80pb by end-2023.”

However, the relationship between the prices of industrial metals and the materials stocks is often weaker, according to Capital Economics. The rise in metals price is partly attributed to the rising production costs led by the surging power prices, which put pressure on companies’ margins and its performance.

The materials sector has underperformed the broader S&P 500 so far in 2022, down 17.9% year to date.

Copper

HGU22,

last Friday tumbled to its weakest level in 20 months as recession fears and China’s weaker-than-expected GDP and trade data continued to weigh on industrial metals prices. China is one of the largest consumers and importers of refined copper, and relies heavily on copper resources to meet its demand for construction and electric vehicles production. Economists at Capital Economics are downbeat about the outlook for the materials sector.

“Admittedly, we do not anticipate big further falls in industrial metals prices, partly because we think China’s metals-intensive economy has now passed a cyclical trough and because we forecast that energy input costs, especially in Europe, will stay very high, as natural gas and coal prices remain elevated,” said Allen. “Even so, our view is that China’s economy will steady, rather than rebound, at the same time as demand elsewhere softens. Although high production costs might support metals prices, they would also continue to be a drag on the profits of materials firms.”