Don’t blame the shrinking U.S. money supply for the bear market in stocks. It’s not that liquidity has nothing to do with stock prices. It’s just that the relationship between them is too complex to be helpful in any straightforward way as a market-timing tool.

This is important to emphasize because this year’s experience is leading many stock-market experts and financial advisers to believe that there is a close correlation between the stock market and the nation’s money supply. The M2 money supply has shrunk 2.7% over the last six months — the lowest six-month growth at least since 1981, which is how far back I was able to obtain weekly data. (M2 includes U.S. cash in circulation, checking deposits, savings deposits under $100,000 and money-market mutual funds.)

The S&P 500

SPX,

has since suffered mightily. At its mid-October low, the U.S. market benchmark was down more than 25% since its early-January high.

Compelling as this narrative is for explaining this year’s bear market, there have been many other past occasions when a shrinking money supply did not lead to a bear market on Wall Street. In fact, there is little consistency to the relationship between the stock market and changes in the money supply. Sometimes a shrinkage led to good stock market years, but other times not. The same has been true for an expanding money supply.

One source of this unstable relationship, I suspect, is that the relationship depends on investors’ attitudes about inflation. When they are on high alert for signs of imminent inflation, for example, then increases in M2 money supply are viewed as bad omens. When investors are instead more worried about deflation, then they celebrate money supply increases.

Fed balance sheet shrinkage

Strongly held beliefs die hard, and one comeback I’ve received to this analysis is that M2 is not the right measure of liquidity on which to focus. A better measure that some have suggested is the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

As was the case with the money supply, there is strong circumstantial evidence in favor of this suggestion. The Fed’s balance sheet mushroomed from less than $4 trillion to more than $7 trillion in the immediate wake of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, and over the subsequent 12 months the S&P 500 nearly doubled. Over the past six months of 2022, in contrast, the Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk 2.2%, as the Fed’s quantitative tightening kicked in. Fewer than 10% of the six-month growth rates over the past two decades were any lower.

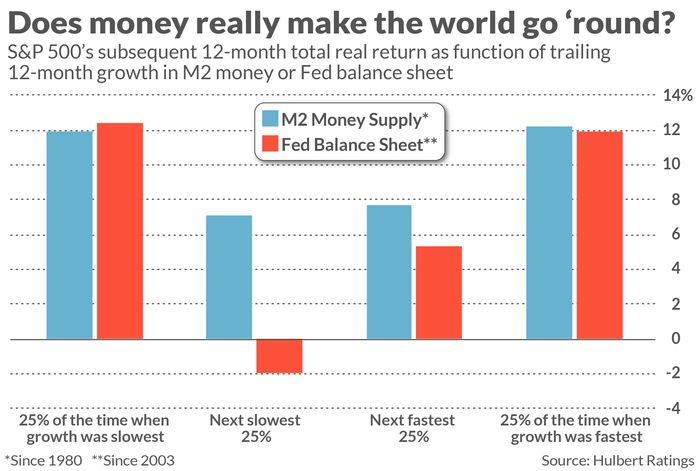

After analyzing the historical data more systematically, it becomes clear that the relationship between the stock market and Fed’s balance sheet is just as unstable as it is with M2 money supply. Sometimes the stock market performed spectacularly following a quickly expanding Fed balance sheet. The same could be said about a shrinking balance sheet. These results are summarized in the chart below.

The broader lesson here is the importance of subjecting our beliefs to statistical scrutiny — regardless of the intuitive plausibility of those beliefs. It makes perfect sense that changes in liquidity would lead to corresponding changes in the stock market. It just happens not to be true in any straightforward or mechanical way that investors can use to beat the market.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected]

More: Technology stocks tumble — this is how you will know when to buy them again

Also read: Municipal bond yields are attractive now — here’s how to figure out if they are right for you