There is nothing wrong in principle with buying stocks for the income they generate, through dividends, instead of growth.

It’s a strategy that’s especially appealing to retirees and others who need to live on the income from their investments.

It’s had long-term success. Multiple studies have shown that so-called “value” stocks, which typically includes companies paying out high dividends in relation to their stock price, have tended to be especially good long-term investments overall.

And as my colleague Philip Van Doorn points out, there may be plenty of attractive opportunities available right now on Wall Street.

But before retirees and income investors wade into the market, there are three things to bear in mind.

Don’t get your hopes up

Dividend yields are still lousy on Wall Street. You won’t get much income in return for your investment.

The dividend yield of a stock is the amount of the annual dividends you get, divided by the price you pay. It can be most obviously compared to the rest of interest you get on a bond or a savings account. Today the “yield” on the entire S&P 500

SPX,

is 1.8%, according to FactSet. That means if you buy $100 worth of an S&P 500 index fund such as the SPDR S&P 500

SPY,

ETF you can expect to get back about $1.80 in dividends (less fees and taxes) over the next 12 months.

That is a full 6.5 percentage points below the current inflation rate. So you’re losing money in real purchasing power terms, at least on the dividends.

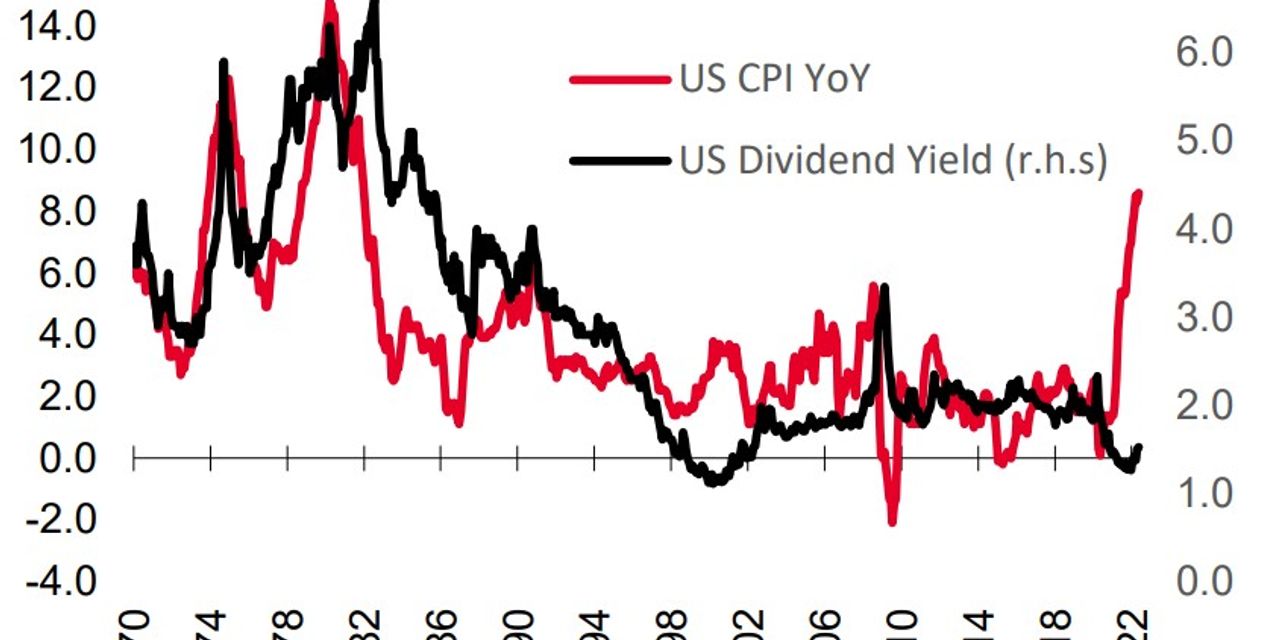

To put this in perspective, according to number cruncher Andrew Lapthorne at SG Securities, the last time inflation was this high — back in the early 1980s—the yield on the S&P 500 was around 5%, or nearly three times as high as it is today. In other words payouts came much closer to keeping up with prices. Stocks were also much cheaper in relation to profits. Stockholders were getting much bigger dividend checks and were getting compensated much more for taking on stock market risk.

OK, so it’s not completely apples-to-apples. Thanks to legal and cultural changes since then, companies try to return money to stockholders by buying back stock as well as paying out dividends. But buybacks aren’t entirely the same as dividends. Studies have shown that companies tend to buy back stock more often at the peak of the market. Buybacks are intermittent, whereas dividends tend to be much steadier. And while companies use cash to buy in stock, they are often quietly shoveling a lot of stock back out again in the form of goodies for the CEO and their buddies on the top floor.

As one of my first news editors used to tell me, back when I was starting out in this business, that dividends have one great advantage over almost every other financial metric companies report, including earnings, revenues, asset values and liabilities: You can’t fake the dividends. The checks go out, or they don’t.

(He knew of what he spoke. He had once worked for a magazine publisher that claimed an audited circulation far above its actual print run.)

The current low dividend yield on the S&P 500 isn’t just about big, high-tech “growth” names that don’t pay out anything, either.

For example the yield on the cheaper, “value” half of the S&P 500 is no great shakes. It’s about 2.7%, according to FactSet data on the iShares S&P 500 Value

IVE,

ETF.

Don’t confuse stocks with bonds

This ought to be written on a Post-It note and stuck to the bathroom mirror of anyone planning to buy a lot of stocks for the income.

Stocks, representing a share of company ownership, are totally different from bonds, which are IOUs issued by the government or corporations. Bonds have a fixed rate of interest and their coupons get paid first, before anything goes to stockholders, in the event of bankruptcy.

As a result, bonds tend to be much, much less volatile than stocks.

Hit a 2008 or March 2020, let alone a 1929, and the stocks in your portfolio will be a sea of red ink.

Yes, bond investors have suffered a similar fate this year, but that tells a story of its own. We have just come out of the biggest bond bubble in history. Bonds paid bupkis at the start of the year, and have since been eviscerated by skyrocketing inflation. It’s been the biggest bond rout on record.

Total losses for the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index

AGG,

this year? Some 13%.

Such a loss in the stock market wouldn’t even count as a bear market. They happen reasonably often. In the worst meltdowns, the S&P 500 or its equivalent can lose half its value or more.

In 2008, at the depth of the panic over the financial crisis, the Barclays Index was down just 12% from its peak.

There are reasons for this: Not just simple animal spirits and panic on Wall Street, but some rational thinking as well. In a deep downturn, dividends can be cut. Or, in many cases, companies will only be able to sustain them by borrowing money—robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Investors looking for income and regarding the paltry yields below 2% in the S&P 500 have other options. You can now earn a steady 5.7% from “BAA” rated corporate bonds, meaning IOUs from companies in the lowest tier of investment grade rating. That is the highest yield since 2011. It still doesn’t match current inflation, but it’s a lot closer. You can earn nearly 4% a year in a 5-year U.S. Treasury Note. And (as I’ve mentioned before) you can get a guaranteed return of inflation plus 1.5% or more by purchasing government-issued TIPS bonds.

Watch out for ‘reaching for yield’

Reaching for yield in this context simply means buying stocks with the highest theoretical dividend yield.

Warren Buffett warns against it, calling it “stupid” if “very human.”

But the late Wall Street guru Ray DeVoe put it best. De Voe, supposedly, was the first to coin the line, “more money has been lost reaching for yield than at the point of a gun.”

Stocks sporting the highest theoretical dividend yields do so for a very good reason: Wall Street doesn’t think those dividends are going to be paid. Not in full, maybe not at all, and maybe not as soon as the next due date. The stock price is cheap in relation to the supposed dividends because the company is in trouble, or is very high risk.

“The higher the dividend the less likely it is to be paid,” reports SG’s Lapthorne. His calculations going back to the early 1990s show that investors typically banked the biggest checks by owning the U.S. stocks in the middle of the pack when it came to yield. Those stocks that appeared to promise the most ended up paying out, on average, very little.

There’s nothing wrong with investing in stocks for income. But it comes with its own risks.