The most recent headline CPI came in at 9.1% so it might seem odd to think that the risk of disinflation and deflation is rising.

But while the CPI is a rearview-looking indicator, many forward-looking indicators are starting to tell a very different story – a story of falling demand and falling prices.

The economic and inflation story of the last 36 months is simple:

- We had a global pandemic that we responded to by printing $7 trillion while we also shutdown huge portions of the global economy.

- This created a mix of demand-side inflation and supply-side inflation.

- While many people thought the inflation would be “transitory,” it has persisted longer than many expected because of the waves of COVID, shutdowns and then the surprising war in the Ukraine.

I am on record having predicted the high-ish inflation in 2020 and 2021, but I was shocked by the persistence of COVID and the War in Ukraine, so inflation has overshot my original upside prediction by a bit. I guess I need to get my crystal ball fixed so it can predict wars and pandemics.

Read: Wholesale prices jump again and signal still-intense inflation in U.S. economy

That said, this doesn’t change my view from a few months back: I still expect inflation to moderate in the coming years, and in fact I think the risk of outright deflation is rising.

As for historical precedents, I think a repeat of the 1970s and the risk of a prolonged period of high inflation is overstated. In fact, I’d argue that the risk of deflation is becoming more and more apparent. This environment looks more like, gulp, 2008 than 1978.

I hesitate to compare anything to the 2008 financial crisis because that was such a unique crisis, but the current period has more similarities than many people want to admit. This includes:

- Booming stock and real-estate markets that have only just started to cool off in recent months.

- Booming commodity prices and uncomfortably high inflation.

- An aggressive Fed that is more worried about runaway inflation than the risk of deflation.

Some people have argued that inflation will be persistent because of wage-price spirals, surging rental rates or a continuation of the COVID supply constraints. And while a worsening war in Ukraine or a war in Taiwan would certainly cause continued high inflation, the baseline at this point appears to be dominated by other higher probability outcomes:

- COVID and its related shutdowns are ending or at least moderating substantially.

- A war in Taiwan looks like an extreme outlier risk.

- Supply chains are improving.

- Demand is slowing across the economy, especially as rate hikes cool the real-estate market.

- Fiscal headwinds will continue well into 2023.

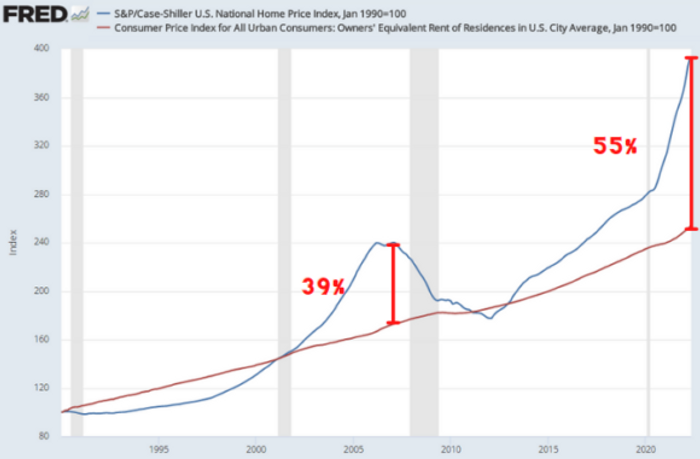

Most importantly, something potentially nefarious is brewing under the surface here and we’re only just starting to see it in the real-estate market.

In short, the Fed’s aggressive reaction to inflation has stalled the housing market at the worst possible time because prices had surged so much. So we have a nasty combination of very high prices combined with suddenly unaffordable mortgage rates.

Federal Reserve Economid Data

The only way this resolves itself is in one of three ways:

- House prices fall substantially.

- Mortgage rates revert to their old rates.

- Some combo of 1 & 2.

As we learned in 2008, housing IS the U.S. economy. So when U.S. housing slows, it will drag down everything with it.

While some are worried that inflation has to continue to surge because price-to-rent ratios are still wide, I believe the risk of deflating home prices will pose a meaningful downside risk to inflation in the coming years.

In fact, investors worried about the exact same thing in 2006-2007 when the price-to-rent ratio was far smaller. This is part of why the Fed overreacted in 2005-2006 and raised rates so much. But what they were really doing was crushing housing demand and creating dysfunction in the credit markets.

That same risk is playing out today.

The kicker here is that the driving force is house prices and house prices are the volatile factor here. Rents lag substantially due to contractual agreements and wage lags. Real and nominal wages are actually deflating thereby putting an upward limit on how much rents can rise. And the softening housing market is going to put downward pressure on house prices.

This means the price-to-rent ratio is likely to converge in the coming years primarily because house prices have downside risk, not because rents have upside risk.

I want to emphasize that I don’t think this is a repeat of the 2008 financial crisis. The underlying housing dynamics are much healthier today than they were back then, but my baseline case continues to be slowing growth and disinflation with a rising risk of deflation if housing weakens more than I expect.

On the flip side, the obvious risk to this forecast is a return to COVID shutdowns, large fiscal stimulus, worsening war in Ukraine and/or a war in Taiwan. But I would argue that disinflation and a rising risk of deflation is more likely than prolonged high inflation.

Cullen Roche is founder and chief investment officer of Discipline Funds, a financial-advisory firm. He is the author of the Pragmatic Capitalism blog, where this column first appeared. Follow him on Twitter @cullenroche.

More from Cullen Roche: It’s now clear that the Federal Reserve has made a huge monetary-policy error