There’s a basic problem with the global financial system — it’s too focused on the U.S. dollar. Yes, the U.S. is the world’s largest economy, but the dollar represents 60% of global foreign exchange reserves and 40% of international trade, despite U.S. GDP representing just a fifth of world output and being a counterparty for roughly 10% of global trade.

And over the years, the U.S. has increasingly weaponized the dollar’s hegemony in the financial system, most recently by freezing Russian reserve assets at the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war. And while not every country is necessarily planning such a belligerent action, not everyone is happy with the U.S. calling the shots.

That’s led to talk that perhaps some other currency, or currencies, could replace the dollar’s role as the reserve currency, or maybe gold or even bitcoin could do the trick, but there’s problems with each of those alternatives, from convertibility in the case of China, to cyclicality in the case of the euro. The fact the U.S. dollar

DXY,

is trading around a 20-year high suggests the market doesn’t treat any rival as a particularly compelling alternative.

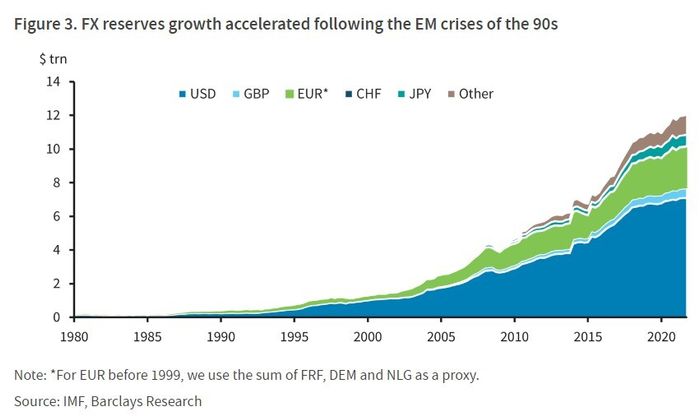

A new report from Barclays suggests a different route — central banks could decide to hold fewer reserves altogether.

It wouldn’t be an easy shift. After emerging market crises during the 1980s and 1990s, countries built up foreign reserves to safeguard their independence, so as not to require International Monetary Fund rescues with inevitable strings attached. The leading foreign-reserve holders have built up war chests that are three times the roughly three to four months worth of imports that the IMF recommends. Most of these countries also get the benefit that their currencies are undervalued, boosting exports.

The Barclays analysts say the alternative is a world with fewer, or no, reserves. That wouldn’t be easy, either. Some countries would adopt protectionist policies, barriers to convertiblity and the like. They would also discourage the build-up of foreign currency liabilities, like dollar-denominated corporate debt, and perhaps encourage the build-up of regional trading hubs.

“Less openness to trade implies suboptimal resource allocation and lower productivity growth. A need to maintain a competitive currency and incentivise local issuance may need to go hand-in-hand with deflationary fiscal policies and low levels of rates,” say Themistoklis Fiotakis, Marek Raczko and Sheryl Dong, all U.K.-based debt analysts at Barclays.

China would face the end of export-driven growth and subdued domestic demand, possibly lifting the value of the yuan. And yields on U.S. debt would inevitably rise. The Barclays analysts say the reserves accumulation has pushed the 10-year Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD10Y,

lower by about 300 basis points since 1990.