The net-zero emissions commitments from Wall Street’s banking giants was a significant step toward holding global warming in check, but in the almost two years since each of the U.S. majors committed to net-zero, their progress remains slow.

That’s a charge advanced in a report out Wednesday from long-established environmental advocacy group The Sierra Club.

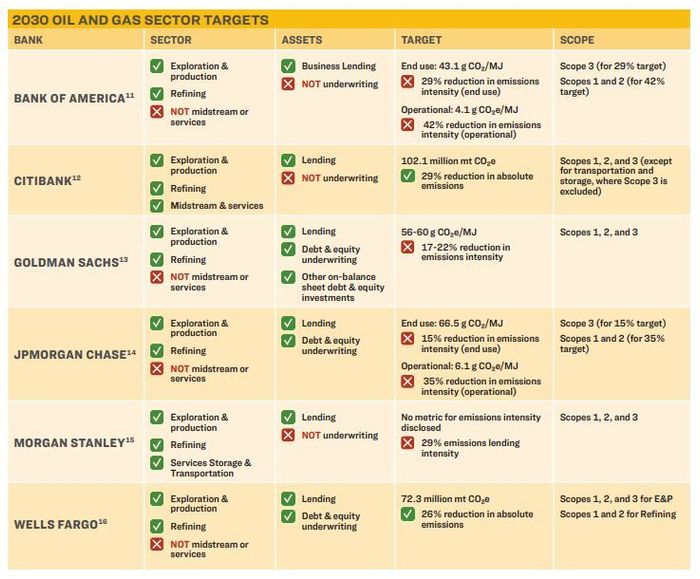

The report examines the banks’ interim 2030 targets to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions not just from their own operations but in how they finance the energy sector and other industrial segments of the economy. The 2030 check-in is meant to show progress on the way to net-zero emissions by 2050, including for the oil and gas

CL00,

and power generation

VPU,

sectors.

“Big U.S. banks have fallen far behind the best practices of their global peers, setting only weak targets and policies riddled with loopholes that allow billions of dollars in new fossil fuels projects each year,” said Adele Shraiman, campaign representative for the Sierra Club’s Fossil-Free Finance campaign. “If banks want to live up to their net-zero pledges, they need to commit to real emissions reductions and end financing for companies expanding fossil fuels.”

The banks in focus are JPMorgan Chase

JPM,

Citigroup

C,

Wells Fargo

WFC,

Bank of America

BAC,

Morgan Stanley

MS,

and Goldman Sachs

GS,

They have provided a quarter of the $4.6 trillion in global fossil fuel financing in the past six years alone.

The Sierra report hits as the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), of which the major U.S. names have joined, is expected to release an update at the United Nations’ major climate change conference, the COP 27, which runs from Nov. 6 to Nov. 18, in Egypt.

The Sierra Club

JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon resoundingly assured lawmakers earlier this year that his bank has no intention of stopping the financing of growth in the oil patch. Dimon, who appeared with other top banking executives on Capitol Hill in September, was asked by Rep. Rashida Tlaib, the Democrat of Michigan, to give a “yes” or “no” response to a handful of questions. That included whether JPMorgan has a policy against funding new oil and gas products.

“Absolutely not and that would be the road to hell for America,” said Dimon, whose bank is the largest U.S. provider of loans and other capital to the energy sector.

The Sierra report suggests there are considerable loopholes in banks’ exclusion policies for drilling in the Arctic. In late 2020, Bank of America was the last to join other U.S. banking majors in saying they’ll refuse to finance oil and gas exploration in the pristine section of Alaska that then President Trump had opened to drilling for the first time ever.

Policy also varies, the report says, when it comes to financing coal projects. Coal remains the largest fossil fuel polluter, but China and India’s slow move away from the fuel and even a resurgence of its use in parts of Europe amid the Russia-sparked energy crisis has aggravated climate-watchers.

The report’s findings also highlight the need for mandatory comparable disclosures of corporate climate commitments, which was feedback that many investors and advocacy groups gave to the Securities and Exchange Commission on its proposed climate risk disclosure rule.

The Sierra Club also values the banking sector disclosing more transparent details. “Of the group, only Wells Fargo has explicitly stated that it does not include [carbon] offsets in its 2030 targets,” the environmental advocates say. Offsets are a primary tool toward net-zero, but some critics worry there will be too much reliance on this mechanism and not moving away from oil and gas.

Bank CEOs may be in a tough spot. They hear from some lawmakers of efforts to remove “woke capitalism” from banking agendas to focus on growth and profits exclusive of other priorities. But they also know that investors and regulators are turning up the pressure to more aggressively fund the transition to renewable energy. If Republicans take the House in the midterms but Democrats keep the Senate, as some polls suggest, the top executives of big financial firms could face climate-change whiplash.

Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan has been asked about the pressure on banks to simply cut the polluters loose.

“Simply saying we’re not going to hold X or Y in our portfolio does not mean X or Y doesn’t keep going on. Getting X or Y to get greener on their steel production every year, or commitments made by the oil and gas industry — not only their operations, but with carbon capture and storage and things that offset their emissions — their change is actually the great change,” he told Politico.

“The binary decision of invest-not invest, lend-not lend, do business with or not do business with — that doesn’t change the behavior of those companies,” he said. “You want those companies to declare net-zero, put a plan on the table. Then society wants to hold them accountable.”

Still, the world’s preeminent climate scientists and select energy experts have stressed that in order to reach global climate goals, all sectors must rapidly and dramatically decrease greenhouse gas emissions. In all, the U.S. economy must slash emissions by around 45% percent by 2030 to keep progress on track for the 2050 marker and to give the globe a real chance to keep the temperature rise below 1.5°C, as laid out in the Paris Accord.

Even an energy industry advocate has spoken up. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in order for the world to limit warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F) by 2050, there should be no additional investment in new fossil fuel supply.

This finding is critical, Sierra Club says, because it means new fossil fuel development is fundamentally incompatible with meeting global climate goals and

with the goals set by the banks themselves.

“Surpassing this threshold is perilous not only for Earth’s climate, ecosystems, and communities, it will also jeopardize the global economy, with current emission trajectories estimating at least 10 percent of total global economic value could be lost by 2050,” Sierra Club said in its release.