Though she applied to college more than 40 years ago, Frida Marte can clearly remember the details of the experience.

She’d come to the U.S. from the Dominican Republic only seven years before and the college process was unfamiliar to her. “I relied a lot on the college advisor,” Marte said. Mr. Block, who was also her U.S. history teacher, pushed Marte to apply to a four-year residential university instead of staying at home and attending community college.

“He kind of encouraged me and gave me the confidence that it would be paid for,” Marte said recently. “He helped me fill out the financial aid application. I brought it to my mom — I was doing the translation — she signed.”

Marte, 62, decided to attend one of those four-year schools — the State University of New York at Stony Brook. She remembers being in her kitchen one Saturday afternoon when she received the award letter indicating that her tuition and expenses would be covered through New York State’s Tuition Assistance Program and funds from the federal government. Marte recalls the name of the federal grant, called the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant, even though in the years since she went to college it’s fallen out of use; it’s now known as the Pell grant.

“I wouldn’t have been able to pay for college, being one of eight children with a single mother had it not been for that Pell grant,” she said. Two of her siblings also used TAP and BEOG to pay for school, Marte added. “We were living on welfare –- that’s how we were able to eat and cover our rent.”

But now, when Marte logs in to her portal on the Department of Education’s financial aid website, there’s no proof that she used the grant she remembers so clearly. “I have navigated the whole internet and I can’t find where I’m supposed to get that information, I don’t know where to go.”

Frida Marte and her son. Marte can’t find evidence of the Pell grant she believed she used on her student aid portal.

Courtesy of Frida Marte

That makes Marte nervous that she won’t get the $20,000 in student debt relief she believes she’s entitled to under the Biden administration’s debt cancellation plan. All borrowers who earn less than $125,000 a year are eligible to have up to $10,000 of their debt forgiven, but those who used a Pell grant, money the federal government provides to low-income students that does not need to be repaid, qualify for an extra $10,000 in relief.

Marte is not alone. Other student loan borrowers who believe they used a Pell grant decades ago can’t find evidence of the grant on their student aid portal, MarketWatch has found, and worry it means they won’t get the full debt cancellation they believe they’re entitled to receive. MarketWatch spoke to student-loan borrowers and advocates suggesting the issue on the Department of Education’s website impacts people who received Pell grants before 1994.

For Marte, there is a lot at stake. If the government discharges $20,000 of her student debt it would be a big help, Marte said. That’s why she was initially “thrilled” when she heard about Biden’s plan. Her son also received a Pell grant when he attended University at Albany, part of the State University of New York system where Marte went to undergrad, but it wasn’t enough to cover all of his costs. She borrowed from the federal government to help finance his education through its Parent PLUS program. Parent PLUS loans have fewer protections than loans students borrow to finance their own education, which means it can be difficult for parent borrowers to find an affordable way to repay the debt.

That’s particularly troubling to Marte, who is retiring soon and will be living in the Bronx borough of New York on about $1,000 a month in government benefits.

“It’s worrying me and keeping me up at night,” Marte said of her student loans. If she’s unable to pay the debt and it slips into default, “they could come back and take that money out of my Social Security.”

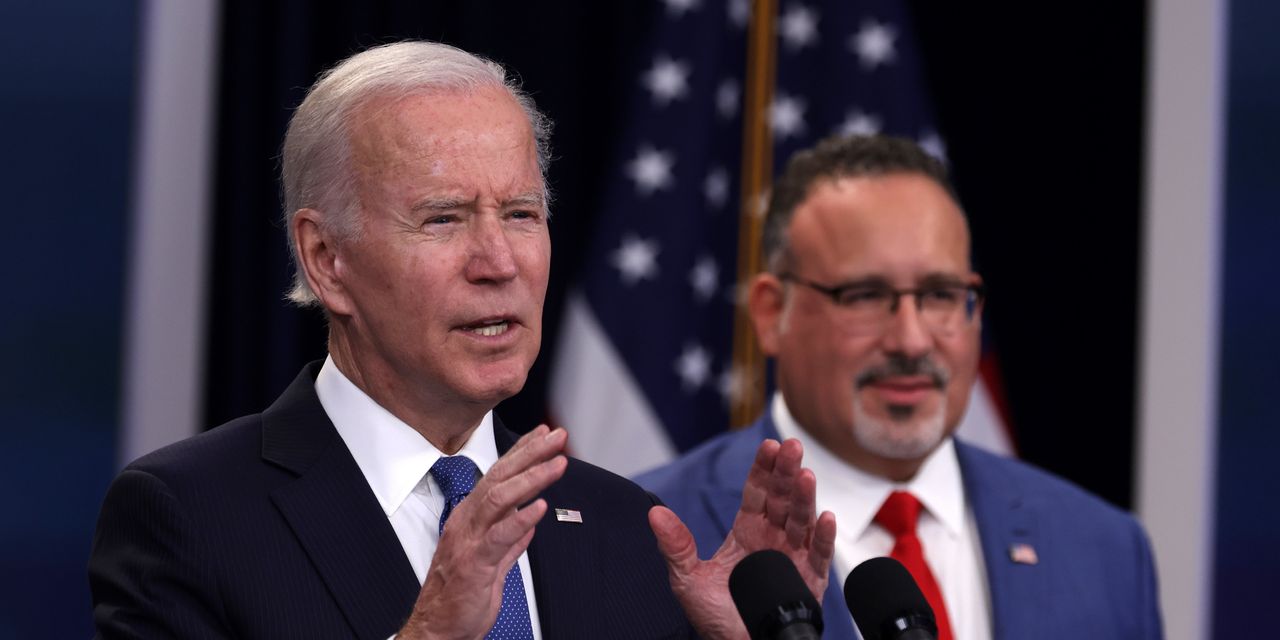

Student loan borrowers celebrated President Biden cancelling student debt, but now some are worried they won’t get the full relief to which they are entitled.

Getty Images

If Marte did indeed receive a Pell grant like she remembers, she’ll get the $20,000 in relief, according to the Department of Education, which didn’t immediately provide comment. “You don’t need to take any additional action to show us that you received a Pell grant,” a Frequently Asked Questions page on the agency’s website advises borrowers. In addition, the debt relief application form doesn’t ask borrowers to list whether they had a Pell grant and a senior administration official confirmed to reporters earlier this month that the agency will be checking whether applicants received a Pell grant.

Still, Thomas Gokey, an organizer with The Debt Collective, a debtor’s union that has been advocating for mass debt cancellation for more than 10 years, said it can be challenging for borrowers to feel confident the program will work as it’s supposed to.

“That old phrase, trust but verify, at this point we have to trust that the Department has the data, the data is accurate, there aren’t errors in it,” Gokey said.

It’s unclear exactly how many borrowers are impacted by this issue. The White House has said of the borrowers eligible to receive relief under the cancellation plan, over 60%, or 27 million, used a Pell grant. Nevertheless, it’s hard to say how many of those borrowers can’t see evidence of their grant on their student aid portal; the issue appears to be isolated to borrowers who used the grant before 1994.

The lack of certainty surrounding the status of relief for borrowers who used Pell grants decades ago is indicative of many of the obstacles facing the Biden administration as they look to implement the one-time cancellation plan and other student loan reform initiatives successfully. Those challenges include, borrower confusion, a lack of faith among borrowers that they’ll get the relief they’re entitled to based on poor past experiences, and a program with dozens of stakeholders and iterations where decades-old decisions can have implications for today.

The Debt Collective recently began organizing student loan borrowers over 50 years old and Gokey said he’s heard from many facing this problem. Gokey said he’s gone deep with about half a dozen borrowers trying to help them navigate this situation. Like MarketWatch, he wasn’t able to confirm they actually received the grant; their colleges likely disposed of student records that are nearly 30 years old at a minimum and the borrowers he spoke with didn’t save any documentation they received a Pell grant.

Did you use a Pell grant before 1994 and have proof? We want to hear from you. Email [email protected].

“There is no way to verify it, pre-1994,” Gokey said. But, he added, “I want to keep it in perspective. The Department of Education probably does have this data and for most people it’s probably accurate, we just know from experience that there are people who fall through the cracks.”

Johnson Tyler, an attorney at Brooklyn Legal Services working with Marte on her student loans, said he would feel more confident if the Department could offer some data on how many people who used pre-1994 Pell grants it expects will be eligible for debt relief.

“This is a conundrum,” Tyler said. “How do you fix this problem? It’s $10,000 that’s on the line. You’re looking at a computer data sheet that doesn’t mention it, so it’s just your word against whoever.”

According to David Bergeron, who left the Department of Education in 2013 after working there for more than three decades, the agency does indeed have the information necessary to confirm that borrowers used Pell grants decades ago.

“As far as I know from my time there, they have records going back to the inception of the program on who received Pell grants and in what amounts for each year,” he said. When he was there the oldest Pell grant data was stored on magnetic tape, a precursor to the floppy disk, Bergeron said.

He does remember one instance during his tenure when “there was some angst” about whether the agency would be able to access one year’s-worth of the data. The tapes, “get brittle and they break so you might have to manually splice together reels of tape to read,” he said.

Bergeron doesn’t know exactly why the Pell grant data from before 1994 doesn’t show up for borrowers when they check the Department’s website, but he said he guesses it’s because current version of the student loan data system was built around 1994 and officials didn’t feel the need to upload all of the records from throughout the history of the program.

Though borrowers may not be able to see these records on the Department’s website, the agency does have a system in place to check this data, Bergeron said. There’s a lifetime cap on how much in Pell grant funds an individual borrower can use; any time a student fills out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, the agency searches the records to see if the borrower has hit their limit, he said.

“They built the infrastructure long ago,” Bergeron said. “The rules have changed over time,” he said of the Pell eligibility cap, “it’s been messy, but the Department has figured out how to deal with it.”

Borrowers likely can’t count on their schools to confirm that they used a Pell grant. Colleges are only required to keep student records for three years after the student is no longer enrolled. The day the Biden administration announced the debt relief program, colleges were “inundated” with calls from former students asking if they’d received a Pell grant and whether the school could provide proof that they’d used a Pell grant, said Karen McCarthy, vice president of public policy and federal relations at the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators.

“The schools were panicking a little bit too,” she said. “They were getting all these phone calls. The Department did in the days after clarify that all of that is in their records and they’ll be double checking that.”

****

Anne McKechnie, 61, said she believes she used a Pell grant in the mid-1980s. She reached out to her school to see if officials could provide her with any documentation that she got the grant and they responded with a form letter.

Unlike Marte, McKechnie isn’t completely sure she used the Pell grant. She said she’s about 80% confident, but what she does remember from her situation at the time makes her feel as if she likely had one. McKechnie went to college after living out of her parents’ home for about six years and was just scraping by and making ends meet. Pell grants are awarded to students with “exceptional financial need.”

“There is in my mind absolutely no way I did not get a Pell grant, I hardly had any loans,” from her undergraduate studies, she said.

Without proof, however, McKechnie can’t be sure she used the grant to pay for college and she doesn’t trust the Department of Education to figure it out correctly because of her previous experience with the student loan system. A public school teacher for 26 years, McKechnie applied for the temporary waiver to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program shortly after the Biden Administration announced it last year.

The aim of the waiver is to fix some of the issues with the beleaguered initiative, which allows borrowers working for the government and certain nonprofits to have their debt forgiven after 10 years of payments, including challenges borrowers faced with having their payments count towards the 120 needed to be eligible for relief.

But in response to her application, McKechnie learned that 28 of her payments didn’t qualify. After that experience, “I thought at least I could get the $20,000 forgiven,” she said and laughed wryly. “I don’t see that’s going to happen because they have bad record-keeping.”

McKechnie has called the Department of Education’s student loan ombudsman, and spent hours on the phone with her student loan servicer trying to suss out whether she’ll have any of her debt canceled under the various relief programs announced by the Biden administration. Her experience going back and forth with these various entities doesn’t make her confident she’ll have any debt forgiven.

“I feel like so much of it is up to me,” she said.

Borrowers’ lack of trust in the government’s ability to deliver on its promises of debt cancellation and the feeling that they have to be on top of their own paperwork if they have any hope of accessing relief has been building for years, Gokey said. The initial rollout of Public Service Loan Forgiveness, in which 99% of applicants were rejected, is just one example of events that have made borrowers skeptical. The first several weeks of implementation of the broad-based debt cancellation didn’t help much, Gokey said. Details of the plan initially dribbled out piecemeal and in October the Department changed the eligibility requirements for relief, potentially shutting out an estimated 770,000 borrowers.

Department officials have said the agency is exploring “additional legally-available options” to allow these borrowers, who have what are called commercially-held FFEL loans, to qualify for the debt cancellation.

“We need to hold them to this and say they need to deliver,” Gokey said. “If they want to ask us to trust them on Pell and other things, they need to deliver on that trust.”

McCarthy said because the Biden administration’s debt cancellation initiative announced in August is much larger than past relief programs, she’s more optimistic that its implementation will go smoothly.

“It is so big and there are so many borrowers that would be affected if this doesn’t go well,” she said. “That would be a very large public relations disaster for the administration, they are motivated to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

But borrowers who believe they used Pell grants to attend college decades ago aren’t so confident they’ll get the relief they think they’re eligible to receive. Patricia C Vener-Saavedra said she remembers applying for and receiving both a Pell grant and a grant from New York’s Tuition Assistance Program to attend Empire State College in the late 1980s.

“I remember being very happy that everything was covered,” she said, noting that she’s about 98% sure she used a Pell grant.

Patricia C Vener-Saavedra doesn’t trust the government to find the Pell grant she believes she received to attend college in the late 1980s.

Courtesy of Patricia C Vener-Saavedra

Vener-Saavedra, 69, later used student loans to attend graduate school and in the time since she’s experienced “moments of panic,” about the debt and at other times, she’s needed some help managing the loans when she faced economic challenges.

“When things got hard, I just started asking for forbearance and everything just got bigger and bigger and bigger,” she said. When a student loan goes into forbearance it pauses payments, but the interest still accrues. Vener-Saavedra said she found it “especially annoying,” when later she learned she could have been using the government’s program that allows borrowers to repay their debt as a percentage of their income during some of this time, but was never told about these plans, where monthly payments count towards forgiveness.

For Vener-Saavedra, who is living on Social Security benefits, receiving the $20,000 in relief would be helpful. But it wouldn’t clear her roughly $88,000 in debt. She recently came across the message on the Department of Education’s FAQ site reassuring borrowers that the agency would find their Pell grant if they used one.

“Prove it,” she said. “Why am I going to trust the government?”