Amid the continuing debate about where inflation is likely to go from here, Jamie Thompson, head of macro scenarios at Oxford Economics, is stepping in with a list of reasons why it could stick around for a long time in the U.S. and abroad.

One big reason is that the “longer inflation stays high, the more embedded it is likely to become,” Thompson wrote in a note released on Tuesday. “While our view is that inflation is likely to recede next year, the outlook is highly uncertain, with evidence underscoring the risk of a more gradual slowing.”

Inflation is likely to remain the No. 1 determinant of whether 2022’s wild volatility in stocks and bonds persists into next year. Central bankers and many forecasters remain optimistic and are clinging to the hope that inflation eventually eases, with the consensus view being that it should drop toward 3% or lower in two years. History, on the other hand, shows that it has taken years for inflation to drop below 6% after it spikes above 8%, as it already has in the U.S., the U.K. and the eurozone. Meanwhile, U.S. households are bracing for a greater chance that inflation stays above 4% over the medium term.

Source: Oxford Economics, Bank of England, European Central Bank, Federal Reserve, others.

“Central banks have been at pains to emphasize that they won’t settle for a sustained period of high inflation. This is borne out by their actions, given central banks’ willingness to pick up the pace of policy tightening even with recession looming over their economies,” Thompson wrote in an email to MarketWatch on Wednesday.

“But central banks could easily be repeatedly surprised by the strength of inflation, should policy rate increases prove less impactful and inflation expectations more sticky than they expect,” Thompson said. “This highlights the risk of significant volatility ahead as central banks feel the need to adjust again and again the stance of policy.”

In a nutshell, here are the seven reasons behind Thompson’s thinking:

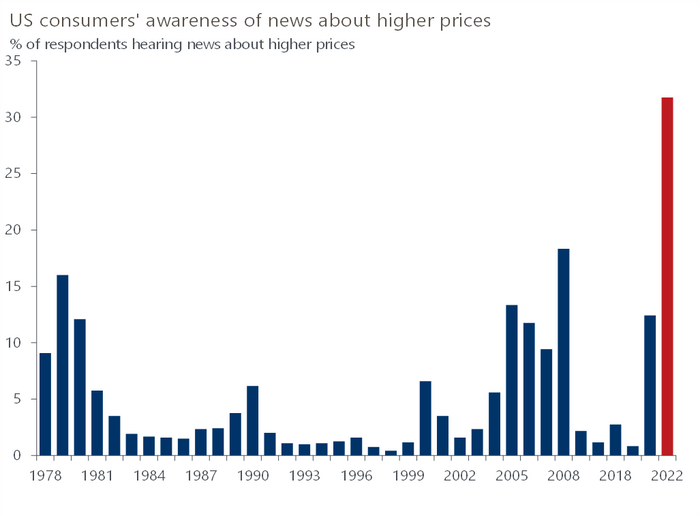

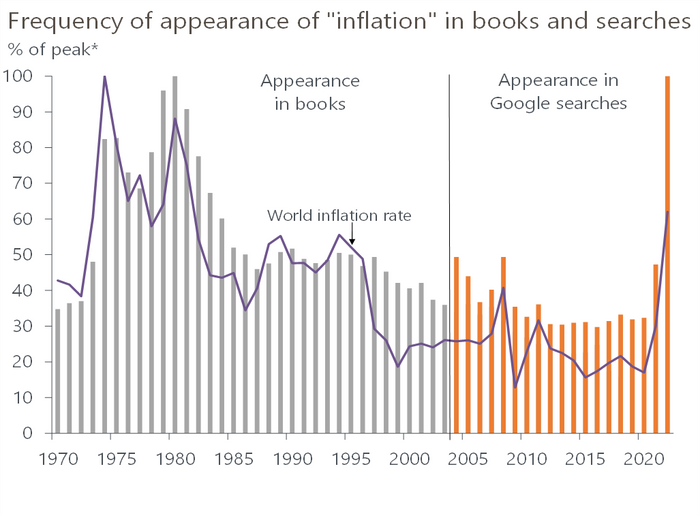

- Public awareness of high inflation keeps growing. That’s leading to signs of a psychological shift similar to the one seen in the 1970s, when changing attitudes about price gains actually caused people to boost their expectations for future inflation — which basically became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Source: Oxford Economics/University of Michigan Survey of Consumers

Source: Oxford Economics, Google, others.

- Many people are expecting inflation to stay high. That’s reflected in most measures of medium-term expectations in which a mix of businesses and households in the U.S., the U.K. and the eurozone expect inflation to be above 2%. To varying degrees across countries, the shift away from central banks’ 2% inflation target “has tended to increase significantly since the pandemic began,” according to Thompson.

- The longer inflation stays high, the more embedded it is likely to become. Oxford Economics’ own Global Risk Survey bears this out: Around two-thirds of businesses reported having, over the past year, raised their expectations for inflation for the medium term. Of those, a majority had also lifted their expectations for inflation in 2023.

Source: Oxford Economics Global Risk Survey, preliminary fourth-quarter results

- Workers are demanding better pay, which risks creating a spiral of ever-rising wages and prices. According to one survey cited by Oxford Economics, more than 40% of U.S. households were planning to ask, or had already asked, for higher wages due to inflation. Similarly, around 40% of U.S. businesses were planning to, or had already, increased wages; more than 50% of them also indicated they intended to, or had already, raised their own prices.

- The public seems mostly unaware of central-bank inflation targets: One survey, taken in April by the research firm Ipsos, showed that only about a third of respondents even knew that the Fed was tasked with price stability. And in a 2021 poll of U.S. chief executive officers last year, only about a quarter were able to identify the general range around the Fed’s 2% inflation target, and “of those who provided an answer, a majority thought the Fed was trying to achieve a higher rate of inflation,” according to Thompson. The final point was true only until inflation reared its head last year and turned out to be more persistent than many expected: The annual headline inflation rate from the consumer-price index has come in above 8% for seven straight months between March and September.

- The public has limited faith, anyway, in the ability of central banks. Only 49% of the U.S. public thinks the Fed makes decisions that are in the best interest of average Americans, according to the April survey by Ipsos. And that fragile faith is important because those people with more negative views of their central bank are less receptive to its messages, Thompson said.

- Finally, in the U.K., where high inflation has created a cost-of-living crisis, there seems to be a lack of support for low inflation. That’s based on the Bank of England’s own Public Attitudes to Inflation survey, which showed only 36% of respondents agreed with the U.K.’s current 2% inflation target. “More people think the inflation target is too low,” said Thompson.

On Wednesday, U.S. stocks

DJIA,

SPX,

were mixed in afternoon trading as investors digested technology companies’ earnings results, a smaller-than-expected rate hike by the Bank of Canada, and the Fed’s most likely path forward. Most Treasury yields fell, with the 10-year rate

TMUBMUSD10Y,

dropping to 4.02%.

Check out: MarketWatch live markets coverage