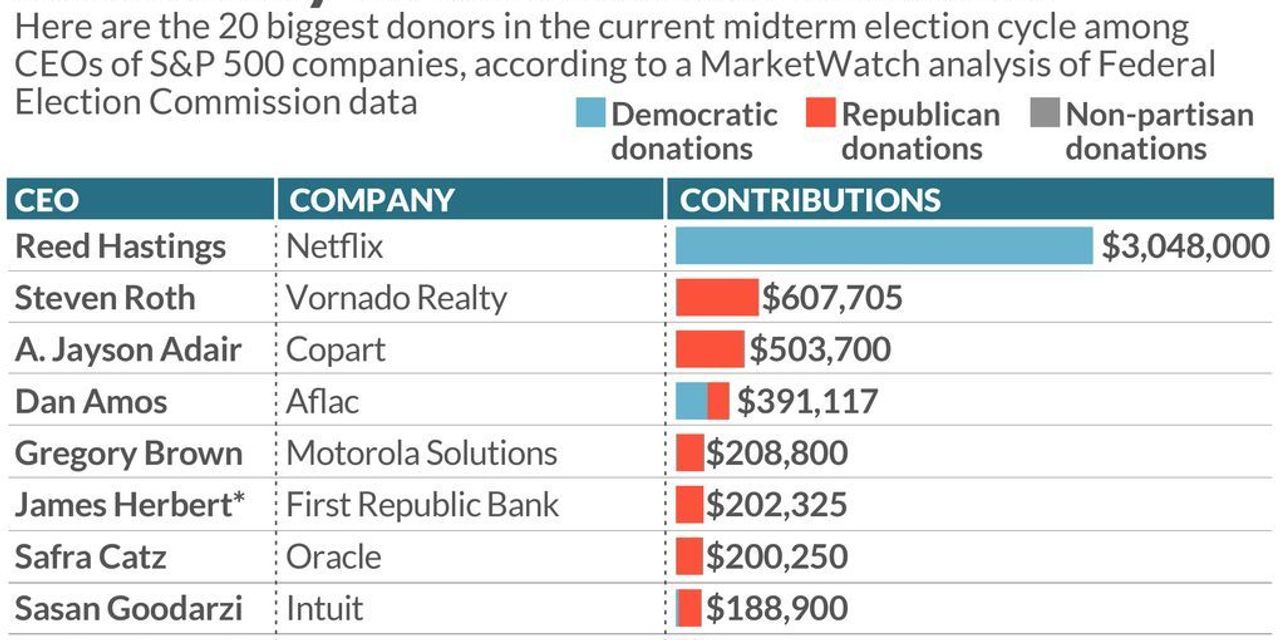

For the past three election cycles, MarketWatch set out to provide readers with a sense of how CEOs of the biggest public companies are influencing American politics by digging into their political giving.

But tallying up an individual’s political donations isn’t straightforward, so we developed a process for mining, matching and analyzing the data. Here’s how we came up with our list.

First, we compiled our list of CEOs, which includes any corporate chief who serves or served in that position for an S&P 500 company between January 1, 2021, and now. Because the S&P 500 isn’t static, we needed to find CEOs who headed companies that may have dropped out of the list during this period.

To find S&P 500 companies that dropped out of the index, MarketWatch researched and manually made note of these changes. Data on who a company’s CEO is and who served as a former CEO plus the effective date of the leadership change comes from FactSet.

Because the Federal Election Commission, which tracks political giving, does not require individuals to have an identification number associated with a person and their donations, we had to search by name and employer to find a CEO’s donations. In addition, donors giving multiple gifts may spell their name or their employer’s name differently for each one. For example, Jayson Adair, CEO of Copart appears in our search in the following ways:

- ADAIR, A JAYSON

- ADAIR, A. JAY

- ADAIR, A. JAYSON

- ADAIR, AARON

- ADAIR, AARON JAYSON

- ADAIR, AARON JAYSON MR.

- ADAIR, JAY

- ADAIR, JAY MR.

And Copart appears in almost as many permutations:

- COPART

- COPART INC

- COPART INC.

- COPART, INC

- COPART, INC

However, we can still do our best to find donations by defining search criteria passed to the FEC’s search API that gives us the greatest chance at finding all donations and by accounting for situations where CEOs choose not to list their employer or decide to list a different company than the one they’re primarily associated with. For example, Jeff Bezos may list his employer as “Blue Origin” rather than “Amazon.” And in a questionable use of the employer field, Elon Musk lists himself as an employee of the Secret Service (“USSS.”)

To eliminate having to search through and process the FEC’s more than 100 million records, we programmed our model to group like-records together and then analyze them further. To get the 100 million plus records down to something more manageable, we wanted to select only rows that exactly match the last name specified to the FEC of one of the 603 unique last names of CEOs in our universe. To do this, we followed the FEC’s recommendation to download the entire bulk data file of individual contributions..

Unfortunately, MarketWatch found the bulk files missing some filings from political committees that we expected to see in our data. As such, we decided to analyze the data a different way and used the FEC’s application programming interface (API), which allows us to make programmatic use of the FEC’s search. The data from the API reflects filings processed by the FEC, and we used it to loop through each last name and an employer query combination we thought would yield the most results.

That allowed us to create a dataset that was similar to what we would have been able to access through the bulk data files, but still include the missing committees.

We then narrowed down our dataset and cleaned it up using a program called OpenRefine to cluster the name/employer matches and determine which ones are matches and which ones are not.

We used the contributor_name, contributor_occupation and contributor_employer fields to determine matches.

Once we were confident in our list of CEOs and contributions, we added information about the committees they donate to.

We used an FEC list of all committees registered with the organization to determine committee designation, committee type, organization type and party.

The FEC does not always assign parties to joint fundraising committees (fundraising efforts by more than one political committee), and leadership PACs (fundraising committees by political office holders) and lobbyist PACs. So, in the FEC committee data, we dug deeper to determine a committee’s political leaning — if they had one.

For joint fundraising committees, we assigned the party to be that of the candidate that the joint committee is tied to. For issue-based committees, we used OpenSecret’s helpful PAC Contribution Data to determine the percentage of donations to parties. If over 90% of donations were to one party, we noted it as such.

While the FEC allows a way to filter out donations that are only from individuals, it doesn’t filter out all transactions from conduit committees. A conduit committee is one that initiates a transfer based on the committee the donor specifies as the recipient. Two of the primary committees that act as conduits are ActBlue and WinRed. We removed duplicates from these two committees from our data.

From there MarketWatch used the data to report on the CEOs who gave the most and Senate candidates in competitive races who received the most from these CEOs.