When the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, one of the federal government’s premier research agencies, last year tapped Richard “Rick” Spinrad as its new administrator, he became — at 67 — the oldest person ever appointed to lead the agency and its 12,000 employees.

Now 68, Spinrad faces a monumental challenge: to muster the best science in support of arresting climate breakdown, even as most scientists agree we are running out of time to head off the worst consequences.

Lately it seems the war is far from being won. The latest State of the Climate report, released at the end of August, shows record concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, ocean heat content and global sea-level rise at record levels as well, while a third of the planet grappled with drought.

“Communities across the nation are facing hurricanes, drought, wildfires, extreme heat and intense flooding,” Spinrad said in a recent statement, “with ecosystems and wildlife threatened by habitat loss, sea level rise, warming waters and a host of other threats from a changing climate.”

Weather disasters wherever you look

In September, while one-third of Pakistan was underwater from monsoon flooding, California remained in drought under a crushing, record-setting heat wave. More than 61 million Americans experienced extreme heat alerts during the late summer.

Next Avenue asked Spinrad about his “mission intractable” and what he brings to the fight. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Next Avenue: A new report projects that by 2050, some 30 U.S. counties will lose more than 10% of their land area to rising seas. What would you say to people who are contemplating moving to traditional retirement magnets like Arizona or the Southeastern coast of the U.S., to that desert oasis or beachfront condo that they’ve been looking forward to?

Richard Spinrad: Being an informed consumer is the short answer. I’m sure, if they’re looking at beachfront condos or raw land to build on, they’re looking at a number of issues like, ‘Where can I get the best mortgage?’ They’re trying to figure out which state has the best treatment of retirement income. Great stuff. I mean, I’ve been there.

See: Climate change is a retirement issue — how to turn worry into action

Less often they’re looking at, ‘What can I expect the climate to be there? Can I expect that sea level rise will be a threat for the actual viability of this piece of land in the coastal environment?’ We put out our sea level rise report with our colleagues at NASA on a regular basis. And the report that just came out in February talks about sea level rise in Virginia Beach being 10 to 12 inches by 2050.

That’s an extraordinarily accurate prediction. Years ago we probably would’ve said something like, ‘Oh, six to 20 inches.’ So if you’re thinking about buying beachfront property in Virginia Beach right now, I would take that literally to the bank and figure out, ‘Hmm, am I gonna have a problem? Am I gonna have regular flooding in my neighborhood?’

So again, it comes back to adding what we call “environmental intelligence” to the suite of other tools that informed consumers will normally use.

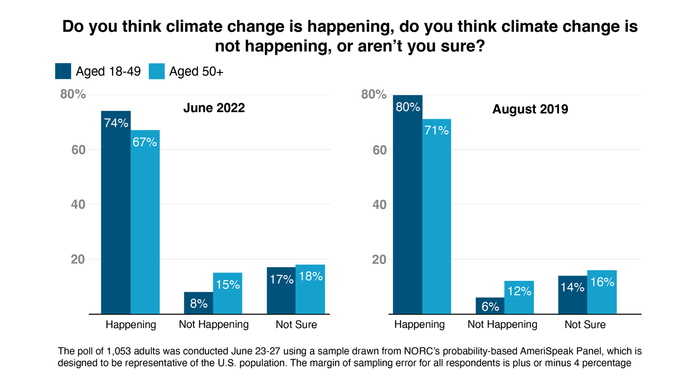

Older adults’ doubts grow

And yet, recent polling appears to show that the number of respondents 50 and over who believe climate change is happening now is smaller than it was in 2019. Fewer also thought that climate change will affect them personally or that individuals are responsible for addressing the issue. It’s got to be hard not to get discouraged when you see trends like that.

The statistics you just shared is, to me, a challenge, a charge for us at an agency like NOAA to get out more. The kind of statistics you’re looking at can turn around if we do a much more aggressive engagement, not by saying, ‘Hey, come read the Journal of Geophysical Research, ‘cuz there’s a really cool paper there,’ but rather saying, ‘How can we get into the room with AARP? With the American Medical Association? How can we ensure there’s a chart of carbon dioxide increase from the Mauna Loa Observatory in my physician’s office?’ So when I go in for my annual checkup, I see it.

AP/NORC at the University of Chicago

So it’s two things. One, it’s geographically dependent on who’s getting hit hardest. And two, it’s a charge to us to reach out to communities that already have the connection with these segments of the population that were polled.

You can imagine this sort of wave of awareness starting to hit different parts of the country differently. I had a meeting with a congressional representative from a very red district just about a month or so ago, who said to me that he’s a fifth-generation farmer and he can’t farm the way his grandfather did.

We’re all paying for it

That’s interesting because it seems like the “wave of awareness” you’re describing is more of a ripple, whereas the climate impacts are already kind of a tsunami.

Absolutely, we feel those impacts. If you take the fires example, who’s paying for that? The fact of the matter is we’re all paying for that, whether it’s the insurance premiums that we pay [or] the medical costs we all pay.

Anybody who believes that they are insulated from the impact of climate change right now is not opening their eyes. It’s impacting their wallet, it’s impacting their availability of food — food security, if you will, along with a number of other issues, including national security.

See: Feeding people on this warming Earth requires future-proofing our agri-food systems. Here’s how.

Oceans of trash

It’s estimated that more than 11 million metric tons of plastic waste ends up in the ocean each year, the equivalent of one fully loaded garbage truck every 45 seconds. Some say this now poses as big a threat to the ocean environment as the climate crisis. How would you describe the threat from discarded plastics?

‘Insidious’ is the short answer, it’s very serious. We don’t even fully understand the impact. There are the iconic images that we have of mammals wrapped up in derelict — or ‘ghost’ fishing gear — that captures a lot of people’s attention. But on the other end of the scale, we’re still trying to understand the impact of microplastics on ecosystems.

That’s why some of the recent legislation like the Save Our Seas 2.0 Act as well as the bipartisan infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act, which have given us at NOAA $200 million of additional resources to address marine pollution — marine debris writ large, but with a real strong focus on plastics — is so important. But I worry about it a lot.

What to do? Everything

And yet, plastics production is projected to quadruple by 2050, so what’s the way out of this?

A lot of folks are saying, ‘No, you gotta address it at the source. It’s about those single-use plastic bottles,’ and others will say, ‘No, you need to go out in the ocean and collect up big nets, all the big stuff.’ Now, others say, ‘No, you gotta really understand what microplastics are doing to what we would call the benthic flora — essentially the stuff on the bottom.’ My answer is: all of the above.

The nice thing is the United Nations has made this a priority. There is increased international activity in this regard. I think we’re to the point where we’re starting to formulate collective activities across nations in the world and, and try to make a dent in this very insidious problem. (Editor’s note: The U.S. is a participant in newly established U.N. talks but was not among 20 nations that formed a “High Ambition Coalition” to “end plastics pollution” by 2040.)

AP/NORC at the University of Chicago

The value of experience

What do you think that, given your age, you were able to bring to the table on this job that a younger person might not?

Brilliance and insight [laughs]. Don’t quote me on that, please.

Too late.

In all seriousness, the experience and insight part — this is actually the argument that I made to Commerce Secretary [Gina] Raimondo when she initially interviewed me for this job. I said we need to start acting on these issues very quickly. Every day we wait, we’re playing even more catch-up.

What you need is people who understand the mission of the agency, where the knobs and dials in the agency are and how Washington works. And also how to relate and work with [Capitol] Hill, the policy makers. Having worked in D.C. since the Reagan administration, I felt like I could come in and hit the ground running and formulate policies and budgets early on.

The other thing that I think I can bring to the table is a level of responsibility. So, you know, I sit in charge of a $7 billion agency in the grand scheme of things. As you well know, Washington doesn’t operate the way we learned in high school civics. It’s really knowing who’s influential, where’s the time and the place to engage.

Boomers’ legacy at stake

It seems like ageism is rampant in our society and also the last form of discrimination that seems acceptable on many levels. What can we do about that?

When you get right down to specifics, people respect the opportunity for my generation, the baby boomers, to bequeath certain things. And so I think there’s a sort of collective ‘last will and testament’ from the baby boomer generation that can talk specifically about what we are going to give to the next generation, and hopefulness in the form of better science to inform decision making is really valuable.

In much the same way that many traditional cultures look to their elders for that sort of traditional knowledge, there’s an interesting parallel here in terms of understanding why it is that a 68-year-old guy in an agency might actually be able to bring something of more value than someone less experienced coming into the job.

Editor’s note: In September NOAA and the Dept. of Interior released a new mapping tool to help communities identify their most serious threats from climate collapse and boost their resilience.

Craig Miller is a veteran journalist based in the northern Catskills of New York. His reporting is focused on climate science and policy, energy and the environment. In 2008 Miller launched and edited the award-winning Climate Watch multimedia initiative for KQED in San Francisco, where he remained a science editor until August of 2019. He’s also a proud member of his local volunteer fire department. Follow him on Twitter @VoxTerra.

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org, © 2022 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. All rights reserved.

More from Next Avenue: